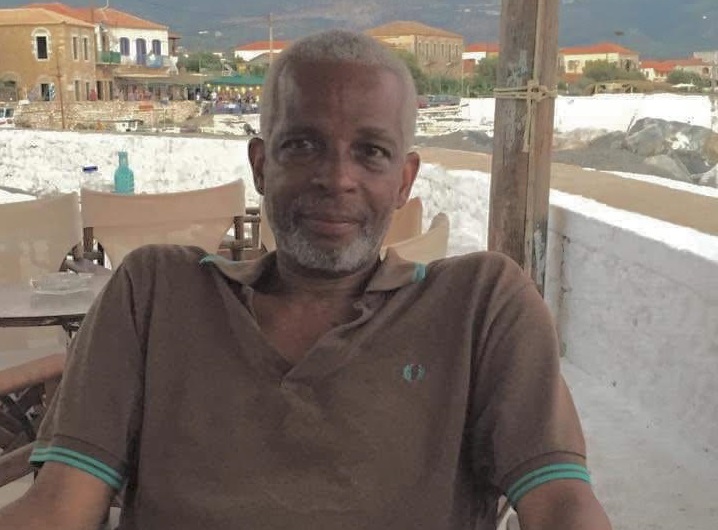

It was with a deep sense of sadness and personal loss that Ana and myself learned of the death of our dear old friend and comrade, Bob Lee, last Friday. We had been very close for many years, and we learned to love and respect him as a great comrade, a tireless fighter and above all as a warm, loving and generous human being.

Our friendship with Bob dates from the early 1980s, when I was obliged for health reasons to leave Spain and return to Britain. Ana and I arrived back in London with no money, a couple of suitcases and nowhere to live. At that time, Bob was living in a small council flat in Bermondsey, not far from London Bridge.

It was very basic accommodation, the kind known at the time as “hard to let”. And it only had one bedroom. But Bob did not hesitate to invite both of us to live there until we could obtain a flat of our own. As if he had not shown us sufficient kindness, Bob insisted on giving us his bed, while he would sleep on a sofa in the front room. We protested energetically against this proposal, but he would hear none of it.

This little incident tells you all you need to know about his characteristic selflessness and generosity. As it happened, it took us longer to obtain a council flat than we had anticipated. But I can say that after several months of living together in cramped conditions, there was never the slightest hint of any problems or friction. Bob was always a very easy-going chap who got on well with almost everybody.

Actually, Bob was frequently away from home. He was often sent away for political work outside London (mainly in Liverpool, as I will explain), but also he had a very intense social life to complement his equally intense political activity. In those brief periods when he was at home (by this time we had been given a small flat right next door), his house was always full of people.

He was a very sociable person who loved having a good time and mixing with people. But this was particularly true at Christmas time, when Bob would go from party to party. Occasionally, this mad social whirl proved too much even for him. He would come to our flat, utterly exhausted, collapsing on the sofa - he jokingly complained that he was suffering from “social fatigue.” He always had a wicked sense of humour.

We had more than politics in common. Bob was a very cultured person who shared our love of classical music.

Political life

From his earliest youth, Bob was a consistent fighter for socialism. As an active member of the Labour Party Young Socialists, he joined the Militant Tendency, where his talent was quickly recognised. He became a full-timer and was put in charge of Militant’s Black and Asian department. Together with comrades like Colin de Freitas and Phil Frampton (who has written a very moving tribute to him), he worked tirelessly to win black and Asian youths to Marxism.

In the early 1980s, Bob was active in the miners’ strike and the big demonstrations against unemployment. He went to Bradford to campaign for Pat Wall, where he played an important role in getting that outstanding Marxist elected to parliament. And all the time, he was active in work among black and Asian youth, including the campaign against the racist SUS laws, the Lewisham and Digbeth marches against the National Front and the Brixton Riots.

But his work met with some very serious obstacles. It was about this time that the pernicious trend that nowadays goes by the name of “identity politics” first raised its ugly head. All kinds of trendy “Lefts” capitulated to this negative phenomenon, which attempts to undermine the revolutionary struggle of the working class by promoting divisions between white and non-white workers, men and women, and so on and so forth. The poisonous consequences of this tendency can be clearly observed today.

Bob had no time for these people. In the 1980s, he waged a tireless struggle against the petty-bourgeois, black nationalist trend, which was advocating the setting up of so-called black sections in the Labour Party. He fought against all manifestations of racism and discrimination, and to advance the cause of people of colour. But as a Marxist, Bob consistently stood for a class position, and opposed all attempts to divide the labour movement along the lines of colour, creed, nationality, language or religion.

During the 1980s, the Militant Tendency led heroic struggles of the people of Liverpool against the vicious cuts of the reactionary Tory government of Margaret Thatcher. They faced ferocious opposition, not just from the Tories and Liberals, but also from the right-wing renegades in the Labour Party, led by the then-leader, Neil Kinnock. The Labour right wing, in turn, was backed by reactionary trade union leaders, and also by fake lefts of the Ken Livingstone variety, who left Liverpool to fight the Tory government on its own.

As part of the efforts of the fake lefts to undermine and sabotage the struggle in Liverpool, an organisation known as the Black Caucus appeared as if from nowhere, attacking the Liverpool Council allegedly from the “left”, complaining that it was ignoring the problems of black people. This vicious smear campaign, which provided valuable ammunition to the right wing, was firmly resisted by Bob Lee, who was sent from London to assist the workers’ campaign.

He did very effective work, although ultimately Liverpool council went down to defeat as a result of the treachery, not only of the right-wing labour and trade union leaders, but also the deliberate sabotage of the fake lefts and the advocates of “identity politics”.

Decline of Militant

Despite its successes, the Militant Tendency suffered a process of internal degeneration, which ultimately led to its demise. The opposition, led by Ted Grant, which attempted to combat the process of bureaucratic degeneration, was expelled in January 1992. At the time, Bob was working in France and did not play an active role in the internal factional struggle. But he became disenchanted with the sectarian politics and bureaucratic regime of Peter Taaffe, and gradually separated himself from the organisation.

I lost contact with Bob for several years, until one evening he unexpectedly turned up on our doorstep in Bermondsey. I remember it was dark, and I did not see him clearly. It was as if he was hanging back, hesitating before knocking on the door. Needless to say, Ana and I welcomed him like a long-lost brother.

That was about 20 years ago, and from that moment onwards, our warm friendship was renewed and strengthened. We were therefore shocked to learn that he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer. Even more tragic was the fact that the cancer had been detected too late to halt its spread. Bob explained that Caribbean men were particularly prone to this horrible illness, and that the doctors had failed to recognise it.

Ana and I kept in contact with Bob and his wife Jo throughout the last year of his life. We invited them for dinner, although later on he began to lose his appetite for food as his health declined. We visited him at his home, and, despite the advance of an illness that deprived him of his strength, making him increasingly tired, he was always anxious to hear the latest news about politics and life in general.

Bob kept his passion for classical music right to the end. He used to have a complete set of LPs of Wagner’s Ring Cycle conducted by the great German conductor, Wilhelm Furtwangler, which he had received from me. Typically, he lent it to someone who, equally typically, never bothered to return it. So when I gave him a new set of Wagner’s Ring, he was delighted.

The last time we visited him was last Monday after an absence of two or three weeks (we were in Spain, looking after Ana’s mother). He was already in hospice. It was a very pleasant place and he was clearly well looked after, but it was also clear that he was approaching the end of his life.

Despite the fact that he could now barely speak, he still asked us to “tell me the news”. So we did, and he smiled. After a while, I asked him whether he was tired, and he shook his head, clearly wanting the conversation to continue. But after a while, he was clearly falling asleep and we took our leave. A few days later, Bob Lee fell asleep for the last time.

His untimely death has robbed us all of a great friend and comrade. Today the world is a poorer place, and humanity has been deprived of one of its finest representatives. A light has gone out in our lives. But we will always remember Bob Lee with a profound sense of joy and gratitude in our hearts for the privilege of knowing such a wonderful person.

On behalf of all the comrades of Socialist Appeal and the IMT, we send our deepest sympathy and condolences to his wife Jo and their children Manu and Olivia, and all of Bob’s family and friends.