On 30 July, Ex-Taiwanese president and former KMT chairman Lee Teng-hui died. Despite being a lifelong KMT bureaucrat, the series of political changes under his presidency in the 1990s earned him praise from bourgeois liberals and a nickname of “Mr. Democracy.” The fact remains that, after the democratic reforms of the 1990s, the KMT still exists as a major party in Taiwan. We take this opportunity to consider how it managed to transform from an apparatus of a dictatorial party-state into a party adapted to a bourgeois democratic system.

At 100 years old, the KMT (Kuomintang, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) is one of the oldest functioning bourgeois parties in the world. During its brief reign in China, it committed some of the bloodiest atrocities against the working class in history, and the Chinese masses’ rejection of it, along with the rottenness of the Chinese bourgeoisie which it serves, would lead to its defeat by the Chinese Revolution of 1949. Yet remnants of the regime would flee to Taiwan and find a second lease on life through the backing of US imperialism and the establishment of a brutal military dictatorship that would not relent until the 1980s.

Despite having conceded to demands for ‘democratisation’ by mass movements, the chameleon-like KMT managed to smoothly adapt to a new environment of bourgeois democracy in Taiwan, and continues to be a major leg of Taiwan’s two-party system to this day. Although recently it is steeped in internal turmoil and has suffered unprecedented electoral defeats, it remains a force within Taiwanese political life that cannot be neglected. A study of how the KMT changed and in turn was changed by Taiwanese capitalism as it struggled for survival throughout the years reveals the fundamental inconsistency of a “democracy” under a capitalist system from the perspective of the working class. Anyone who genuinely fights for a fully democratic society must understand that a consistent democracy is only possible under a socialist society and a workers’ state, which are necessary to permanently defeat the interests that the KMT represents, and finally hold these criminals to account for what they have done.

Chiang Kai-shek and the KMT as a Bonapartist regime in Taiwan

On the eve of its defeat by Mao, the KMT in China was doubtlessly a party serving the Chinese bourgeoisie, starting from Chiang Kai-shek’s wife Soong Mei-ling’s tycoon family. The Chinese bourgeoisie, like their counterparts in colonial and semi-colonial countries, were rendered by imperialism into servile compradors that were completely incapable of achieving progressive tasks for the nation they claimed to represent. The KMT, as the political apparatus that defends this class’ interests, is equally incapable and uninterested in carrying out progressive democratic tasks in government, but is completely focused on repressing workers and peasants’ movements. At the end of WWII, the post-war economic crisis in China led the already rotten edifices of Chinese capitalism to collapse upon themselves. The titanic peasant movements the Chinese Communist Party took leadership of would push over the house of cards that was the KMT regime.

With survival instinct as strong as that of cockroaches, Chiang, a portion of the Chinese bourgeoisie and state bureaucrats refused to go down easily. They brought along with them enormous sums of wealth and hundreds of thousands of soldiers (many of whom were forced conscripts), and refugees to Taiwan: an island they gained control over from Japan in 1945. The entire state apparatus of the Republic of China, which was founded after the Chinese Revolution of 1912 and deeply fused with the KMT, was moved to Taiwan.

Nonetheless, Taiwan was far from a safe haven for the KMT regime. Having endured US bombardments during WWII, the Taiwanese people were given a deeply corrupt, authoritarian, yet chaotically run provincial government that the KMT set up, beginning in 1946. This rapidly ratcheted up popular anger among the Taiwanese masses that culminated into the February Revolution of 1947. Chiang deployed troops from China to drown this struggle in blood, in what became known as the 228 Massacre, but although the revolution was defeated, the ferment in Taiwanese society against the KMT persisted.

After installing himself in Taiwan, Chiang Kai-shek was aware of the party’s shortcomings, as well as its lack of support among the Taiwanese population. To quickly ground himself in Taiwan and prepare for a counter-attack against Mao, Chiang ordered a series of restructurings of the KMT and the governance of Taiwan in an effort to penetrate, monitor, and control Taiwanese society. At the same time, the KMT enforced a series of relatively progressive bourgeois reforms that it was unwilling to enforce while in China in order to dissipate the ferment among the masses. Many of these changes were strongly encouraged by US imperialism, who enforced similar policies around East Asia in an effort to contain the spread of revolution.

Within the party, the KMT was restructured into a significantly more centralised party, eliminating the possibility for separate factional apparatuses that existed before. The central party apparatus was placed under the firm grip of Chiang and his closest allies, while the party also branched out into party cells at the neighborhood level in order to recruit and train native Taiwanese KMT cadres. This party structure was particularly effective in penetrating urban populations, especially in schools and professional circles. It was, however, poor at extending the party’s influence in rural areas and among workers.[1]

Today, many bourgeois academics and politicians refer to this party structure as “Leninism.” This cannot be further from the truth. Unlike a real Leninist party founded upon the principle of democratic centralism, where all party policy is up for democratic discussion and debate to the freest extent by members, Chiang modeled his party on a top-down military structure and used it as a monitor-and-control mechanism.

Outside of the party itself, in order to more tightly control the workers, the KMT facetiously allowed the formation of labour unions, under tight supervision. With an unwritten rule of the general secretary having to be a mainlander, the board of directors having to be a native Taiwanese, and both KMT party members, unions were strictly enforced. The KMT government also offered a large array of insurance policies and benefits to workers, which were not particularly costly, as industrial workers only accounted for a minority of the total population in Taiwan in 1952.[2] These government-monitored “unions” could not carry out real union functions such as striking, and in effect were tools for the KMT to recruit more members and mobilise votes during local elections, [3] as party members enjoy more perks in the workplaces. Notably, this strategy did not succeed in winning over enthusiastic new worker recruits, and most workers who joined the party held an ambivalent attitude towards the party’s politics. As a KMT cadre once reported:

“The political level among worker comrades tended to be low. At the time they tended to join the party organisation in groups while having no idea what the (party’s) ideologies are, and were purely motivated by securing their job positions. After they’ve joined the Party, they did not get rigorous training, and normally would not receive correct leadership and rectifications. After a time they inevitably became tired of (the Party) and shirked their duties (as members).”[4]

Chiang Kai-shek and the KMT, supported by US imperialism, were forced to grant massive concessions on the agrarian questions in Taiwan in order to maintain its regime after being defeated by the Chinese Revolution / Image: 姚琢奇 public domain

Chiang Kai-shek and the KMT, supported by US imperialism, were forced to grant massive concessions on the agrarian questions in Taiwan in order to maintain its regime after being defeated by the Chinese Revolution / Image: 姚琢奇 public domain

With respect to rural elites and peasants, the KMT followed Japan’s example and embarked on a series of rent reduction policies and “lands-to-the-tiller” programmes to win over the peasantry while buying off the landlords. This enormous project was possible due to the massive financial and technical aid from the US, with American experts directly hired to be staffed on the Sino-American Joint Commission on Rural Reconstruction (JCRR), which oversaw much of the land reforms in Taiwan. Out of the five commissioners of the JCRR, two of whom were directly appointed by the US President. Between 1951 to 1963, over 24 percent of the US non-military financial aid to the KMT regime in Taiwan went to the JCRR, which in turn used the majority of these funds towards investments in agriculture projects.[5] At the end of these land reforms, over two million Taiwanese gained land property, and the income of peasants almost doubled, while productivity of agriculture increased by 50 percent.[6]

In effect, in an effort to prevent revolution, the KMT and US imperialism had to complete the basic capitalist task of land redivision in Taiwan, which was not carried out under Japanese colonialism. Not only did this enormous state intervention cut across the ferment among the peasants against the regime, it also laid the ground for a subsequent capitalist boom in Taiwan.

Nevertheless, the majority of the peasantry were still strongly influenced by their local elites, who dominated farmer associations since Japanese colonialism and held tremendous influence over local affairs. In order to absorb these local clientelist networks into its fold, the KMT began to hold extremely limited local elections.

The local elections were one of the most important mechanisms for the KMT to assimilate the local bourgeoisie to help it control rural Taiwan. Local elites already held a significant amount of mobilising power in their territories, and therefore could easily command votes from the peasants within their sphere. The gentry has always held a tight grip over the peasants in service to whatever state is in power. The most illustrative example was the Koo family of Lukang. Koo Hsian-jung practically designed the neighborhood administration network known as Hoko by the Japanese imperialists, while his descendant Koo Chen-fu became a KMT grandee that even met with CCP representative Wang Daohan on behalf of the KMT in a series of negotiations known as then “Koo-Wang Summit” in 1993. To this day, the “Koos Group” remains a major corporation in Taiwan. The clientelist networks operated by gentry families such as the Koos remain a key tool for vote mobilisation on behalf of both bourgeois parties.

The KMT allowed these elites to win the local elections to provide them prestige and legitimacy, and later invite them to join the party, a strategy that proved successful.[7] Notably, as a legacy of the 228 Massacre, most anti-KMT Taiwanese elites were purged. Anti-KMT Taiwanese elites were largely petty bourgeois types, including physicians, lawyers and other professionals. As a result, those local elites whom the KMT was able to recruit were predominantly larger bourgeois elements, such as businessmen and landlords.[8]

The result of this series of KMT restructuring efforts was that it gradually gained control over the Taiwanese population through penetrating the urban populace and coming to control the rural areas through co-opting local elites. At the same time, the KMT created an appearance of legitimacy by fashioning itself as a membership party bent on retaking China through the ideological strength of Sun Yat-sen’s “Three Principles of the People”, and touting its increasing number of rank-and-file cadre who were native Taiwanese. This balancing act between the classes in society was a typical display of bourgeois Bonapartism.

Bonapartism describes a situation where class struggle is elevated to a level that threatens the system of class rule itself, the bourgeois state would raise itself above workers, peasants, and the bourgeoisie, ruling by force and strike down on all classes, but with the final aim of maintaining the rulership of the ruling class and their system. Leon Trotsky once described the Bonapartist state as follows:

“A government does not cease being the clerk of the property-owners. Yet the clerk sits on the back of the boss, rubs his neck raw and does not hesitate at times to dig his boots into his face.”[9]

Chiang’s rule as dictator was Bonapartist in nature and in that way founded upon maintaining his base within Taiwan. The KMT on the one hand appeared to punish the local gentry in favor of the people by redistributing the landlords’ lands, while on the other managing to co-opt bourgeois elements into its ranks. At the same time, the KMT’s structure was actually an ever-expanding bureaucracy that policed every aspect of society. Where this was successful, the working class was taken in by the series of seemingly friendly gestures from the KMT to relinquish their resistance, while the local ruling class was invited to join the new club of oppressors.

The KMT state machine marshalled enough power to monitor urban life, control the labour unions, win over farmers and local elites and incorporate friendly Taiwanese bourgeoisie into its fold while crushing the ones who opposed it. For the other half of society that stood against it, the KMT police state used violence, detention, expulsion and execution to stamp out opposition.

Nonetheless, Bonapartism as a form of bourgeois rule cannot be maintained indefinitely. Historically speaking, the world bourgeoisie found the most favorable form of the state, or as the Communist Manifesto puts it the “committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie,” to be bourgeois democracies. As John Peterson explains:

“The ideal form of bourgeois state is the democratic republic, which allows for profit-making and control of the working majority of the population through the rule of law, force of habit, tradition, playing one section of the population off another, and the judicious use of force. Compare this to the open reaction of a military dictatorship, which, while defending capitalism in the face of political and social ferment, inevitably distorts the normal operation of the system, and therefore cannot last as long.”

The KMT could not resist this inevitable historical process, but it successfully found a way to adapt to these changes as Taiwan’s capitalist economy developed.

The KMT and development of balance of forces in Taiwan

The capitalist economy would continue to develop in Taiwan under strong intervention by the KMT state. In the early 1950s, state-owned enterprises produced over 56 percent of Taiwan’s industrial output. The state controlled key sectors such as water, electricity, gas, the railroads, telecommunications, petroleum, metal, and fertiliser industries, while maintaining an export-oriented economy connected to the world market. At the same time, it granted assistance or loans to private enterprises owned by local clients submissive to the party. Starting from the 1970s however, many private businesses within higher value-added industries, such as plastic and electronics, began to emerge.[10] With this came a layer of the bourgeoisie that controlled a larger share of Taiwan’s economic development and therefore a more assertive position against the KMT state bureaucracy from within and outside of the party.

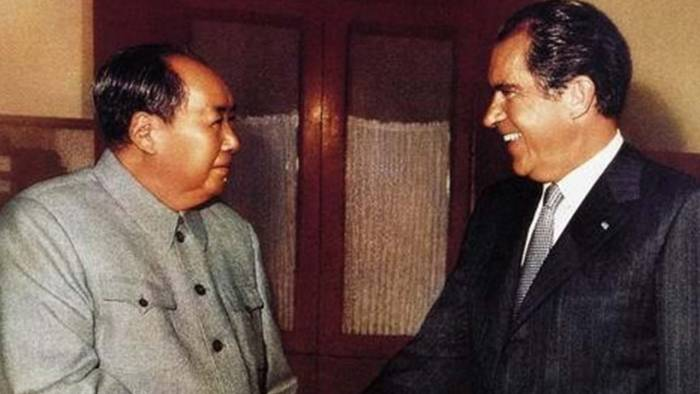

Another key pillar of the KMT’s rule in Taiwan, the backing of US imperialism, was also eroding away as the US shifted its strategy in Asia. Chiang Kai-Shek had, of course, been a solid “anti-communist” ally of the US (although sometimes the latter had to halt Chiang’s insane attempts at retaking China militarily). After the US suffered a defeat in Vietnam while the Sino-Soviet conflict persisted, the strategists of US imperialism began to consider Mao to be a more useful counterweight against the USSR compared to the Chiang regime. The Chinese Communist Party and the US started to take a series of steps towards collaboration at the expense of the KMT, beginning with Henry Kissenger and Richard Nixon’s visits to Beijing, then the state of Republic of China being forced out of the United Nations with US acquiescence, and finally culminating in the US breaking formal diplomatic relations with the KMT regime in 1979. This series of humiliations that the KMT suffered internationally would then motivate more people from within Taiwan to question its power.

US imperialism’s rapprochement with China dealt a serious blow to the KMT regime’s authority / Image: Image fair use

US imperialism’s rapprochement with China dealt a serious blow to the KMT regime’s authority / Image: Image fair use

The pressure from the rising Dangwai movement

The loosening of the KMT’s omnipotent image from all these factors began to dawn on the masses in the late 1970s, which led to the emboldening of a heterogeneous anti-government movement that was previously operating under clandestine conditions, known as Dangwai, or “outside-of-the-Party” movement. The activists of this movement encompassed a kaleidoscope of tendencies, from liberal-democratic intelligentsia, to Taiwanese nationalists, radical leftists (many sympathetic to the CCP), and various bourgeois or petit-bourgeois elements dissatisfied with the KMT. This movement of contradictory tendencies found unity in their opposition against the KMT’s regime, but those with liberal leanings, often with privileged class backgrounds, began to gain a larger share of voice within the Dangwai movement.[11] This movement would later culminate into the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP).

The development of the movement that became the DPP and its leadership’s actual role is beyond the scope of this article. What can be summed up is the fact that the various activists of this contradictory tendency played a role in inspiring the masses that channelled various class aspirations under the umbrella of a single “anti-KMT” banner. Various episodes of secret yet well-attended meetings, often held under bridges, took place.

Some prominent leaders of this movement stood for elections as “independents” (as no party other than the KMT was legal). Where the KMT tried to rig the election result against highly popular Dangwai figures, mass revolts ensued. In the 1977 Zhongli Incident, the masses favoured Hsu Hsin-liang, who, despite having recently defected from the KMT, actually won the election of Taoyuan county governor by a landslide, but was declared defeated after obvious vote-rigging. This ignited struggles that culminated in the burning down of a police station by the masses. The KMT relented in the end, invariably emboldening the movement.[12]

During the Zhongli Incident, the masses protested KMT vote-rigging by burning down a police station / Image: 台灣民報邱萬興提供

During the Zhongli Incident, the masses protested KMT vote-rigging by burning down a police station / Image: 台灣民報邱萬興提供

More significantly, workers in the industrial regions of Taoyuan-Hsinchu-Miaoli area began to struggle against the KMT’s state-union system in the 1980s, inaugurating what is known as the “autonomous union movement.” Active worker militants successfully began to take over some union leaderships or formed their own. This shook the KMT regime and the big Taiwanese bourgeoisie alike. Eight Taiwanese tycoons, headed by Formosa Plastics Corporation chairman Wang Yung-ching, issued a statement calling on the government to deal with the labor struggles. Wang himself threatened an investment strike.[13] This movement yielded the finest labor leaders in the history of Taiwanese class struggle, among them Taoyuan bus driver Zeng Maoxing. Despite the state’s brutal crackdown on these labour struggles, the pressure from below was clearly felt by the KMT.

Under the threat of revolution, the KMT, all the way up to Chiang Kai-shek’s son and successor Chiang Ching-kuo, initiated a series of processes that would preserve the party in a new era in Taiwan.

Lee Teng-hui and internal changes within the KMT

Along with the mounting pressures from the grassroots, the KMT was undergoing internal changes as well. As time passed and the elderly Chinese-born faction leaders of KMT withered away, the newly emergent native Taiwanese bourgeoisie began to grow in number and influence within the KMT. With the capitalist economic liberalisation and the boom of the 1980s that saw the private sector becoming the dominant force in Taiwanese economy against state-run enterprises, native Taiwanese within the KMT started to wrestle away the central party apparatus traditionally helmed by Mainland Chinese or their descendants.

Yet adapting to such a development was already accepted by the KMT at its highest level. The pivotal figure in this process was Lee Teng-hui. Born during the Japanese colonial period in Taiwan, Lee was a Taiwanese-born member of the KMT with education from Cornell University who rose through the ranks of KMT bureaucracy as an expert in agriculture throughout the years, eventually earning the attention of Chiang Ching-Kuo. At this time, the adroit junior Chiang probably realised that the KMT could not rule as it had before. In order for the KMT to survive, the Taiwanese bourgeoisie had to have a larger say in the party and government. Thus, much to the chagrin of the various KMT aristocrats and elites, Lee became Chiang’s Vice President in 1984, and succeeded Chiang after his death as the president of the ROC and chairman of the KMT in 1988. Chiang Junior also made a major step in ending the decades-long martial law imposed on Taiwan, freeing more movements to flourish. The threat of revolution from below led to concessions from above.

Lee’s administration played another important Bonapartist act within the party’s development that ultimately ensured the party’s own survival. Contrasting with the past leadership of the KMT that barked orders to the Taiwanese masses in unfamiliar regional Chinese dialects, Lee was a native Taiwanese that could demagogically present himself as a fellow countryman. He also played the various KMT grandees, especially the Premier with military background Hau Pei-tsun and Ex-Premier Lee Huan, off against each other, while making concessions to the growing mass movements, mainly the Wild Lily student movement of 1990, in order to safeguard the survival of the state of the ROC and capitalism itself. Thus, political parties outside of the KMT began to consolidate and compete in bourgeois elections within the confines of the law, even taking seats and positions not previously possible. Simultaneously, the KMT under Lee’s leadership pushed forward one constitutional amendment after another that would shape the legal basis for Taiwan’s liberal bourgeois democracy today, most notably the establishment of direct presidential elections in May 1992, which was to come into effect in 1996.[14]

At the same time, the mainstream bourgeoisie in Taiwan found a greater source of income from investments in China, which concurrently opened itself up to foreign investments, especially those from Chinese-speaking capitalists, as a part of the capitalist restoration efforts led by the governing CCP. The CCP no longer views the Taiwanese bourgeoisie with a political allegiance to the KMT to be mortal enemies and US-agents, but preferable capitalist allies against the forces of what the CCP considered to be “separatists” in the DPP. This pivoted the KMT from a historical nemesis of the CCP to their most reliable political agent within Taiwan. In the early 1990s, Lee’s party leadership facilitated some of the most important reapproachments with the CCP, including the 1993 Koo-Wang Summit, and a secret meeting in Hong Kong in 1992 called the “92 Consensus” that reiterates the principle of Taiwan is a part of “One China.”[15] To this day, both the CCP and the KMT would repeatedly cite the “92 Consensus” against Taiwanese independence.

Chiang Ching-kuo (left) and Lee Teng-hui (right) played pivotal roles in the transformations of the ROC state and the KMT that would ultimately preserve the KMT / Image: fair use

Chiang Ching-kuo (left) and Lee Teng-hui (right) played pivotal roles in the transformations of the ROC state and the KMT that would ultimately preserve the KMT / Image: fair use

This culminated in the 1996 general election, when the KMT nominated the Taiwanese-born Lee Teng-hui to be its presidential candidate against his primary opponent: the DPP’s meek candidate Peng Ming-min. The fact that Lee was able to preemptively achieve some key democratic reforms won him popular support. At the same time, the CCP threatened missile bombardment of Taiwan in an effort to stop Lee from getting elected, as they were suspicious of Lee individually playing up his Taiwanese origin and flirting with slogans of “localisation” prior to the election as signs of Lee’s deviation from One China Policy. This plan backfired on the CCP: the Taiwanese masses were angered rather than cowed by this threat. In the end, Lee won the first bourgeois democratic presidential election in Taiwan by a landslide as the KMT’s candidate. This gained the party not only four more years of government, but a status of a “normal” bourgeois party that would be able to stand in elections as a major force in the days to come.

A cunning bourgeois politician, Lee’s measures earned him significant bad will from within the KMT, which was expressed in the emergence of opposition factions such as the “New KMT Alliance” in late 1989. Later, KMT grandees Lin Yang-kang and Hau Pei-tsun stood as candidates against Lee in the 1996 presidential election. Thus, in the later period of his tenure as president, Lee began to significantly ramp up pro-Taiwanese independence demagogy, contradicting the principle of unification with China that the KMT holds sacred. He was subsequently expelled by the KMT and, bizarrely, became a revered figure within Taiwanese independence movement, despite his track record. Lee and his cohorts became notable power brokers of the “Green” DPP camp.

In modern KMT historiography, Lee is branded as a Judas-esque turncoat. Yet objectively, it is undeniable that without the role Lee played in the 1990s, the KMT would not have been able to survive against the tidal wave of mass movements, nor acquired its new role as the pro-China political agent in Taiwan. In a highly comparable situation to the Spanish Transition, the old forces of Francoist reaction still were forced to reorganise their party into a “new” one: the Partido Popular, while the KMT maintains its own organisation and traditional networks better than its Spanish counterparts.

These changes meant that the KMT and the system of capitalism itself in Taiwan, maintained through the state of the Republic of China, could continue to exist. The concurrent change in the regional and world situation relegated Taiwan into a buffer state between the competing influences of China and the US. In this context, the KMT found another purpose to exist: to represent the interests of the bourgeoisie, especially those who wish to enter into the Chinese market. Despite the formidable workers’ movement that emerged in the 1980s, it never developed an independent political expression. Therefore, the primary leadership of mass movements against the KMT was still petit-bourgeois liberals, who preferred to confine the struggles within legal boundaries rather than unleashing the masses. They also never questioned the system of capitalism, narrowly limiting their goals on “improving” Taiwanese capitalism into a more democratic form. Thus, the KMT was able to live for another day, with a new role in Taiwanese society.

The KMT since the 90s: a zombie lurching ahead

With the shifts in the 1990s and the DPP taking presidency for the first time in 2000 as a then-consolidated bourgeois party, the KMT’s main appeal to the masses in the complete absence of a workers’ alternative became chiefly their close relationship with the growing power of China. Under the concurrent global decline of capitalism and its effect on stagnating the Taiwanese economy, the KMT could present itself as the “pragmatic” option that can approach the CCP and continue the Taiwanese economy’s growth by leaning on the Chinese economy, which the DPP could not do as the CCP refused to work with any party that wouldn’t repudiate support for Taiwanese independence. In the 2000s, the KMT maintained its parliamentary majority and even regained the presidency through democratic elections with Ma Ying-jeou in 2008 and again in 2012. In the to-and-fro between these two camps of bourgeois political forces at national and regional levels, the KMT and DPP enforced the very same bourgeois policies.

All of this came to a head in 2014, when the growing contradiction of capitalism itself and the threat of Chinese imperialism became unbearable. This pressure cooker led to the enormous Sunflower Movement that opposed the KMT’s Ma Ying-jeou administration’s illegal, undemocratic tactic to force through a wide-ranging trade agreement with China that many thought would devastate the Taiwanese service industry and place much of the economy under Chinese influence. The KMT since then suffered one mortal defeat after another and was set into enormous internal turmoil, only gaining a momentary respite in the 2018 regional elections. This was because they were the only alternative for voters to “punish” the DPP for its equally pro-capitalist policies, against the backdrop of an exacerbating capitalist crisis.

In 2018, the KMT thought that it found a savior in Han Kuo-yu. Han is a bizarre third-tier “anti-establishment” demagogue known for his socially reactionary positions and a talent for right-wing populist rhetoric, not unlike Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro. With such an image, Han was able to win the mayoral campaign of Kaohsiung, a city which had solidly voted DPP for decades, by a landslide. This feat soon propelled him to be the KMT’s presidential candidate for the election of 2020, to the chagrin of the party establishment, made up of “respectable ladies and gentlemen,” in the absence of any candidate that had such demagogic appeal, even when FoxConn CEO Terry Kuo tried to compete with Han in the party’s primary election.

From a party of the “respectable” bourgeois ladies and gentlemen, the KMT today has degenerated to a hive of buffoonish characters / Image: 陳玉珍官方臉頁

From a party of the “respectable” bourgeois ladies and gentlemen, the KMT today has degenerated to a hive of buffoonish characters / Image: 陳玉珍官方臉頁

Unfortunately for Han and the KMT, they were not able to profit from the confusion and lack of alternative in the same way that Han’s American and Brazilian counterparts did. The eruption of the movement in Hong Kong again reminded the Taiwanese masses of the immediate threat that China poses to the democratic rights of the Taiwanese people. Han was not able to work his magic and cover up the pro-China stance that his party defends. Han and the KMT suffered a massive defeat against the DPP in both presidential and parliamentary elections in early 2020.

Thus far this year, under the pressure of the COVID-19 pandemic, the KMT is reduced to a parliamentary fraction that reasserts its existence through stunts, while watching the DPP absolute majority government enforcing much of the policies that it designed. It remains in steep internal turmoil, with a supposedly “youth” faction led by current chairman Johnny Chiang (no relation to the notorious Chiang family) that is willing to distance itself from the CCP presently on top, while extreme pro-China KMT politicians go as far as appearing on TV shows in China to denounce the DPP. There is also a populist reactionary, yet small, activist base that lurks within the party’s ranks.

At the very best, the KMT could only hope for a bizarrely chaotic existence of the British Conservative Party: one that used to be the envy of bourgeoisie of the world, but today lives as a hive of buffoonish characters. But we should also remember that even in such degenerate form, the British Tories remain in power through electoral victories thanks to the failure of the left reformist opposition leaders. In the absence of a militant, socialist workers’ political alternative, the KMT could very well be propelled back to power somehow within the present bourgeois democratic system of the ROC.

The comparison of the KMT to a cockroach thus remains apt. Ultimately, vermin find a way to survive under all conditions: and thrive in the most filthy. A suitably putrid environment is provided by the decomposing capitalist system that lords over Taiwan and the world. If the Taiwanese activists truly believe in the popular slogan “If the KMT doesn’t fall Taiwan would not be good,” then they must realize that Taiwan and the world will only be good without capitalism. A workers’ democracy and an international socialist society are the only means to cleanse our lives of this filth once and for all.

Notes

[1] Lin Chia-lung, Path to Democracy: Taiwan in Comparative Perspective, Diss., Yale University, (Ann Arbor: UMI, 1998), p125-136.

[2] Ibid., p123.

[3] Ibid., p122.

[4] 何明修,《支離破碎的團結:戰後台灣煉油廠與糖廠的勞工》,

[5] 蔡石山,《台灣農民運動與土地改革》,1924-1951,

[6] Denny Roy,《台灣政治史》,中文版,台北,2004,p136

[7] Lin, 142.

[8] Ibid., 151.

[9] Leon Trotsky, “Von Papen & Hitler Bonapartism and Fascism,” in The Militant 5.34 (1932), Marxists.org, Web, 7 May 2015, <undefined

[10] 王振寰、李宗榮、陳琮淵,“台灣經濟發展中的國家角色:

[11] Linda Gail Arrigo, “The Social Origins of the Taiwan Democratic Movement: The Making of Formosa Magazine, 1979”, original July 1981; revised March 1992, p4-12, <undefined

[12] Ibid., p9

[13] 何雪影,《台灣自主工會運動史 1987-1989》,亞洲專訊中心,香港,1992,

[14] Roy, p249-259

[15] Roy, p292