The following interview with Ulrich Kolbe is centered on his friend and comrade, Harry Fisher. Ulrich played a major role in promoting Harry's story worldwide by translating his books Comrades – Tales of a Brigadista in the Spanish Civil War and Legacy into German.

The Abraham Lincoln BrigadeHarry was a veteran of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, an all-volunteer force made up of more than 2,000 American workers and students who went to Spain during that country's Civil War, in order to fight fascism. The ALB was originally established by the Communist Party USA in their small office on Manhattan's Lower East Side.

The Abraham Lincoln BrigadeHarry was a veteran of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, an all-volunteer force made up of more than 2,000 American workers and students who went to Spain during that country's Civil War, in order to fight fascism. The ALB was originally established by the Communist Party USA in their small office on Manhattan's Lower East Side.

Although the party had already undergone the process of Stalinist degeneration, the workers who made up its ranks were convinced that they were fighting for socialism. Due to the authority of the Russian Revolution, many thousands had entered the Communist Party and Young Communist League on the basis of their loyalty to the original program of Lenin and the Revolution.

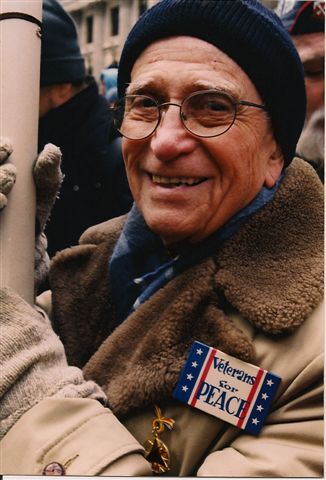

Harry FisherThe best of those members in the 1930's were to be found in the Spanish trenches. Since Stalin and his bureaucracy had zig-zagged from their earlier "Third Period" ultra-leftism to the so-called "Popular Front" alliances with the bourgeois radicals and republicans, the American fighters in Spain knew that the goal of the International Brigades was not to establish socialism in Spain, but to stop the march of fascism across Europe. Here, Ulrich recalls Harry, who died at the ripe old age of 92 in 2003, after participating in an anti-war demonstration in New York City.

Harry FisherThe best of those members in the 1930's were to be found in the Spanish trenches. Since Stalin and his bureaucracy had zig-zagged from their earlier "Third Period" ultra-leftism to the so-called "Popular Front" alliances with the bourgeois radicals and republicans, the American fighters in Spain knew that the goal of the International Brigades was not to establish socialism in Spain, but to stop the march of fascism across Europe. Here, Ulrich recalls Harry, who died at the ripe old age of 92 in 2003, after participating in an anti-war demonstration in New York City.

KB: Tell us how you first heard of Harry and what prompted you to get in touch with him.

UK: Well, like many others, I had read his 1997 book Comrades – Tales of a Brigadiasta in the Spanish Civil War. Having always been interested in the International Brigades, I knew quite a few other books on that topic. Interestingly, Steve Nelson’s The Volunteers was published in my country, the GDR, in English and German, at about the same time he was being tried in Pennsylvania under the Sedition and Smith Acts.

Back in 2000, the annual Reunion of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade organization in New York City featured a program by Pete Seeger, his grandson Tao, and Arlo Guthrie. East German students had learned 'We Shall Overcome' and 'If I had A Hammer' in our English classes, so it was time for me to go there.

Eleven years after the defeat of the deformed workers states in Eastern Europe, we had to fly halfway across the world to hear, in what we had always considered the world’s center of imperialism – New York City, antifascist German labor songs and to witness an auditorium of seven hundred people standing up to sing the Internationale together. We met Milt Wolff, the last Commander of the Lincolns, and Moe Fishman, then secretary of the VALB organization. I asked them whether by any chance I could have just seen Harry Fisher among the vets. I remembered Harry’s picture on the back cover of this above-mentioned book and was not even sure whether the author would still be alive.

Moe answered, “Sure, he’s the fella’ over there wearing the red tie. Go ahead and tell him how much you liked his book. He may wanna hear that.” And that’s how we first met.

KB: It seems he lived a very difficult early life, growing up in an orphanage and then beginning work at a young age. Is there anything Harry shared with you about his time as a boy that sticks out in your mind?

UK: While traveling from one corner of Germany to the other, visiting thirteen cities on his 2001 reading tour, Harry told me quite a number of personal stories, some of which are in his second book Legacy, and some of which are not. The ones I remember most vividly were about his becoming a non-believer and actually interested in the ideas of socialism as a result of the beatings and his pedophile and sadistic supervisors at the orphanage. Contrary to many others, he did not grow to be bitter, disillusioned, or frustrated – not even after his subsequent experiences in Spain. His humanism was deeply rooted and came with a unique, good-natured humor.

Time and again he explained why after Spain he would never again say he was hungry or thirsty – for it was there that he had experienced these feelings for real.

KB: How did Harry first get into socialist politics, around what time was that and what organization did he join?

UK: Harry always stressed the fact that he had never read any books by Marx or Lenin before joining the YPSL. Still, he was made President of the SP’s Norman Thomas Club without knowing the first thing about socialism. He was looking for alternatives to the orphan-home-style or religion-based activities, and the Socialist Youth offered just that. It was probably more class instinct than class consciousness at that time. Soon, he came to the conclusion that the YPSLs were merely a debating club, and his witnessing a group of YCLers actively helping evicted families was probably one of the experiences that radicalized him.

KB: In his books, Spain obviously plays a central role in Harry's life. Having met or known of other veterans of the International Brigades in the GDR, what makes Harry stand out in your mind?

UK: When I first met Harry, I was amazed by his youthful, humorous, easy-going approach. This was not a man of 90 years; he was an activist young at heart and full of energy.

In the country where I grew up, schools, streets, barracks were named after German and International Brigadistas, and there was a lot of official honoring of them. We learned and sang their songs at school. Sadly, many of those brave Germans who survived not only the Spanish Civil War but also the fascist concentration camps afterwards were integrated into the Stalinist East German bureaucracy, some of them losing touch to the people and their ideals. Unfortunately, some – not all – German brigadistas became apparatchiks, making it harder for the younger generation to talk to them, actually meet them, identify with them.

In the U.S., the returning international volunteers had their passports taken away from them, were considered “premature antifascists” and not allowed in government jobs, were persecuted under McCarthy – yet apart from a handful who became “friendly witnesses” for McCarthy or published disgusting lies, most of them lived on true to their ideals even though they were never officially rewarded for their deeds and beliefs like in my country.

KB: I understand Harry also fought in the Second World War. A lot of those who were sent to Europe really believed that the US was waging war against fascism, especially those who were in the Communist Party and bought the Moscow Line. Was Harry one of those? Did he ever change his understanding of why the US was in the War?

UK: I think he was quite disillusioned in this from the onset. He knew that Roosevelt’s appeasement and non-intervention in Spain had enabled Franco, Hitler, and Mussolini to win. Had the U.S. seriously wanted to stop fascism, it could have and would have gotten involved earlier. Also, genuine U.S. antifascists had seen the rise of fascism in their own country, the rise of Father Coughlin’s hateful messages. While not a member of the CP, Harry did see fascism as a product of imperialism, and the U.S. was an imperialist country as well. While serving with the USAAF, he – like many others – fought to accomplish what in Spain had been denied to them as a result of the western “democracies” withholding support, to defeat fascism.

KB: When Harry came back from the War he worked for Tass, the Soviet news agency in New York. I understand he left the CP but never stopped calling himself a Communist. Can you touch on Harry's disillusionment with Stalinism?

UK: Well, he once told me – based on a statement of Pete Seeger, I believe – that he wanted to be referred to, if at all, as a communist with a lower-case “c”. He was neither a party member nor did he follow some party line as an apparatchik. Like many socialists and communists back then, he read the Daily Worker. Contrary to us in Eastern Europe, Khrushchev's speech at the XXII Party Congress must have had a devastating impact on progressives here. I would compare the effects of this to the results the per-war Hitler-Stalin Pact had had on many communists in Germany who were already forced into illegal activities. The Stalinist information policies – that we in the GDR experienced firsthand as well – must have played a key role for his disillusionment for sure. It started right after the war and culminated in the USSR’s basically refusing to report about the nuclear incident on Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania – fearing it would trigger concerns among its people about the Soviet nuclear technology. Still, we must not forget that at this time the Soviet Union along with the other deformed workers states in Eastern Europe were considered by many the only allies for the labor movement in developed capitalist countries and for the national liberation movements in other parts of the world. I think this idea made it possible for many to excuse Stalinism for so long.

KB: I read that Harry was reluctant to meet you at first. Can you explain why and what changed?

UK: Yes, this is true. When I first approached him at the auditorium in NYC in April 2000 and introduced myself, he asked “Why are you in Germany?” And yes, he was not all that interested in reading my first letter.

I guess his wonderful family, his children as well as his grandchildren played an important role in adjusting his attitude toward Germany, as probably did his ability to communicate extraordinarily well with people in many different countries.

As he always explained it to me, it was one of the most wonderful and important lessons for him at that late a point in his life to realize that even we may fall for biases, and that we have to fight them and overcome them. He was forever thankful for having met a large number of what he called “good” Germans – people who attended his readings during his tour of Germany, and for having this wonderful experience at UZ-Pressefest, the biannual festival hosted by the (formerly West) German CP.

KB: What do you think are the most important lessons of your friend's life? How can we apply them today?

UK: I have good friends in Germany and other countries in Europe and Asia who consider themselves progressives, lefties, or even Marxists, yet still can’t help condemning entire countries for evil politics of some. Signs of lacking interest, nationalism, xenophobia or distrust, whatever we may call it.

We have to understand that a better world is possible, yes. And it means just that, the whole world. It is vitally important for people in Africa and Asia to know that they have friends and comrades in the U.S. and Western Europe.

Another lesson – don’t get discouraged, keep up the good fight. And you are never too young and never too old for that.

Solidarity, and our grand old slogan, Workers of all countries, unite.