Xie Xuehong (Hsieh Shue-hong, 謝雪紅) was a key figure in the revolutionary movement in Taiwan in the early 20th century. Despite having to fight against the tremendous barriers that a backward patriarchal society placed before an impoverished, illiterate peasant woman, she was able to found and build the Taiwanese Communist Party (TCP, 台灣共產黨).

Although she was trained ideologically within the Communist International, whose thinking was heavily distorted by Stalinism, her revolutionary sincerity helped lead her to conclusions that approached genuine Bolshevism. This eventually put her on a collision course with her party co-leaders, who continued to adhere to Stalinist orthodoxy.

Figures similar to her – who instinctively moved in the direction of adopting genuine revolutionary ideas without fully grasping the essence of Bolshevism, its method or theory – are common in revolutionary history. In that sense she was similar to figures like Che Guevara, Amilcar Cabral and Fred Hampton, revolutionaries who, unfortunately, never drew all the necessary conclusions. Although these figures could achieve big successes at times and stumble upon this or that correct policy, because they did not have a well-rounded training in genuine Marxism, they ultimately made some fundamental errors. This in turn led to the most unfortunate of defeats in crucial moments.

Xie’s political experiences were no different, and thus have a general application beyond simply understanding Taiwanese revolutionary history. Her political life carries crucial lessons about revolutionary method, tactics and strategy, which are just as applicable in today’s conditions as during her lifetime.

Taiwan radicalising under Japanese colonialism

In order to understand Xie’s political life, it is first necessary to understand the specific conditions of Taiwanese society. A small island in close proximity to the larger, more developed societies of China and Japan, it reflected the large-scale social processes of its neighbours, but in an extremely concentrated form. The repeated waves of invasions by external forces – several Chinese dynasties, Spain, Netherlands and finally Japanese imperialism – meant that Taiwan experienced a combined and uneven historical development. While its general development was severely retarded, the foreign powers also brought some of the most advanced methods of production to the island.

In demographics and culture, Taiwan is also very diverse. First settled by Austronesian aboriginal people, they were then joined by waves of immigrants – mostly poor peasants, many of them outlaws – from southern China, especially Fujian and Guangdong. They imported with them their traditional peasant relations. After the Sino-Japanese War of 1894, Japanese imperialism became the dominant force on the island, decisively shaping the particular form of its transition to capitalism. Understanding these peculiarities, which shaped the new working class in Taiwan and gave their organisations unique features, is crucial.

For the most part, Japan exported monopolistic agricultural corporations, or Zaibatsus (財閥), into Taiwan. This development resulted in a capitalist economy that nevertheless had the peasantry as the vast majority of the population. In 1920 the peasantry was 70% of the population, while industrial workers, relatively underdeveloped in comparison with the west, made up only 8.9% of the population.[1]

The Japanese installed an authoritarian Colonial Government that treated the Taiwanese majority as second-class citizens in their own home. Their rule was supported by Taiwanese big landowners and bourgeoisie who organised the neighbourhood-based surveillance Hoko (保甲) system, which punished entire neighbourhoods if the slightest anti-Japanese activities were discovered there. Aboriginal people in the mountains were further subjected to harsh and dangerous forced labour.

In these conditions, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 became a great source of inspiration for a whole generation of workers and youth to look to socialism as a means of their own liberation. Woodrow Wilson’s support for the right of self-determination, although demagogic in nature and not referring to Asia, also emboldened a layer of liberal Taiwanese bourgeois and petty bourgeois to begin organising political activities in the 1920s to petition the Japanese government to grant more rights to Taiwanese citizens.

Many groups formed, which initially started out as typical bourgeois and petty-bourgeois political outfits. However, faced with the brutal opposition of the imperialists and the domestic capitalists, they would rapidly radicalise and grow beyond their initial liberal aspirations, changing their class base and their political program in the process. One such example was the Taiwan Cultural Association (台灣文化協會). Founded in 1921 with a sizeable membership of 1,031, it was formed by liberal Taiwanese petit-bourgeois intellectuals with the aim of promoting and defending Taiwanese national consciousness and preventing the full Japanisation of Taiwanese society through legal, non-violent means.

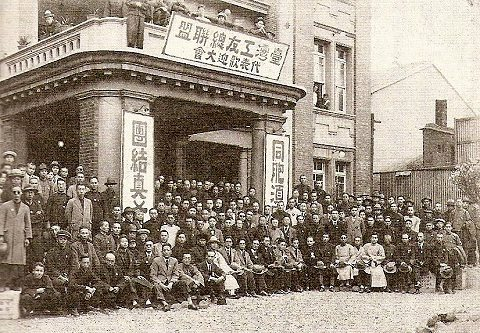

First Leadership Council of the Taiwan Cultural Association, comprising future leaders of both left-wing and right-wing movements / Image: public domain

First Leadership Council of the Taiwan Cultural Association, comprising future leaders of both left-wing and right-wing movements / Image: public domain

Ideologically diffuse, this group included different tendencies, at first mixed indiscriminately in a hodgepodge, that only gradually took shape and distinguished themselves. On the right wing was landlord Lin Xiantang (林獻堂). The reformist labour wing later crystallised around Dr. Jiang Weishui (Chiang Wei-shui, 蔣渭水). The radical labour wing was exemplified in future TCP member Li Yingzhang (李應章,aka 李偉光).[2] Although right-winger Lin was elected as the leader of this organisation, the development of the ferment in Taiwan, expressed through high school and university student movements, quickly pushed the ranks to the left. The right wing then split away, transforming the nature of the organisation decisively.

From child marriage to communism

It was from this background of radicalisation of society that Xie Xuehong stepped into revolutionary politics. Xie’s early life was defined by two struggles: her struggle against poverty, and her struggle against the barbarous patriarchal customs that the “more civilized” Japanese imperialism maintained in Taiwan for its own interests. She was born into an extremely poor, illiterate family in today’s Changhua(彰化), a small city in central Taiwan. Overwork and disease drove her parents to an early grave, and, at the age of 13, Xie was bartered away as a “child bride” (Tongyangxi, 童養媳) in return for funeral costs. Later, she was “purchased” once more by the rich travelling merchant Zhang Shumin (張樹敏).

Her social position throughout this was little better than that of a slave, forced to do whatever hard labour her husband or husband’s family saw fit to load on her back. Her second husband was no better. Characterised by sleaziness and incompetence he, nonetheless, did take Xie along on his business trips to Japan and China, providing her with valuable experiences that shaped her revolutionary consciousness.

The 1918 Rice Riots (米騒動) in Kobe, Japan were the first events to radicalise Xie. At the time, Japan was undergoing an economic crisis. Rice merchants purchased crops from farmers at extremely low prices, only to horde them in turn and ratcheted up the market price, even at the cost of causing food shortages. Finally, the ferment exploded. Farmers rose up against rice merchants and the government, while workers went on strike. The Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake (寺内 正毅) was forced to step down to quell the mass movements. Bearing witness to this magnificent episode of struggle, Xie, who previously thought that oppression was an eternal fact of life, first learned that it was possible and necessary to stand up to the powers that be.

Her second and most transformative experience came soon after, in Qingdao, China. The titanic May 4th Movement (五四運動) was raging on. Millions of Chinese workers, peasants, and youths stood up against the imperialist forces. It was also at this time that the ideas of Marxism began to spread in China. In Qingdao, Xie encountered some radical students who were agitating against Japanese imperialism, and promoting support for the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War. She was deeply moved by the October Revolution and how the Russian working class had taken power and had become masters of their own destiny.

The May Fourth Movement radicalised youth & workers of China, pushing many towards the Russian Revolution and Marxism, thus creating the conditions for Xie’s encounter with the ideas of October / Image: public domain

The May Fourth Movement radicalised youth & workers of China, pushing many towards the Russian Revolution and Marxism, thus creating the conditions for Xie’s encounter with the ideas of October / Image: public domain

That was when she decided to give herself a new name, Xuehong (Snow Red or “Turning the Snow Red”) – taken from a picture depicting wounded Russian revolutionaries turning the snow red with their blood – as a pledge to dedicate herself to revolutionary politics.[3] This was a symbol of her breaking free from the old patriarchal shackles; having grown up with dehumanising non-names such as 假女 (not-woman) and 阿女 (that-woman), this was the first real name she ever had.

During trips between Taiwan and Shanghai, Xie became acquainted with her future lover and co-founder of the TCP, Lin Mushun (林木順). Together, the two of them journeyed from a generic left-wing nationalism towards a more consciously developed Communism, finally joining the Communist Youth League in Hangzhou, China. Although the League was at the time politically and organisationally submerged into the Kuomintang (KMT), which represented the interests of the Chinese bourgeoisie and foreign imperialists,[4] Xie could see the superiority of the Communists over the KMT. Her pauperised upbringing, and early experiences with the limits of bourgeois liberalism, convinced her of the primacy of a class-based outlook. Meanwhile she divorced her husband, embarking instead on a lifetime dedicated to the cause of socialism.

Xie’s political education and the role of the individual

Xie came to play an enormous personal role in the development of Communism in Taiwan, but throughout her life we also see how she came to embody the greater social forces at play in the world around her. Being from a poor destitute background her life sharply contrasted with that of most of her party comrades who were from wealthier educated layers. Xie only learned to read in her 20s and although she had an excellent class instinct, she often found it hard to formulate herself confidently. She herself described this as a constant dead weight holding her back.[5] Despite quickly becoming a key organiser in Chinese Communist Party (CCP) led public mobilisation efforts and in building the Cultural Association inside Taiwan, she did not take the spotlight. In the initial stages of the TCP’s work she would prefer to let other people write the theoretical documents, focusing her forces on organisational tasks.

At the same time, the Stalinist degeneration of the Third International increased the pressures of sexism and chauvinism inside the organisation. After Lenin’s death, the practice of demanding women Communists who were pregnant or with child to become housewives for their partners began to spread among foreign Communist students studying in Moscow.[6] These reactionary ideas, which the Russian Revolution had previously fought against, was now actively fostered by the growing bureaucracy in its own interests. When she later became the leader of the TCP, some of the other leaders of the organisation, such as Su Xin (蘇新), would deeply resent being led by a woman.[7] This was ultimately used in the toxic factionalism and manoeuvring which later developed against Xie.

Xie and her comrades taking a group photo before setting off to Moscow. Xie sits in the front row, the second from the right / Image: public domain

Xie and her comrades taking a group photo before setting off to Moscow. Xie sits in the front row, the second from the right / Image: public domain

The biggest limitation placed upon her, however, was the Stalinist political education and leadership she received from the Comintern. When she arrived in Moscow in 1925, the Russian Revolution had been isolated in a large, backward country and had undergone years of foreign invasions and a bloody civil war. The failures of the revolutions in the west forced the world’s first workers’ state to struggle alone in extremely limited conditions, which led to the rise of a caste of bureaucrats that used their positions to gain privilege in society. This caste, which found its best representative in the person of Stalin, would go on to adopt one anti-Marxist position after another, domestically and internationally, to maintain their privileges at the expense of the working class. Political leaders such a Trotsky, who represented the genuine traditions of Bolshevism, came under attack, were sidelined and slandered.

For the inexperienced Communist parties around the world, the Comintern would become a bureaucratic taskmaster that ordered them to make one mistake after another. In China, the Comintern adopted the class collaborationist approach towards the bourgeois KMT, and ordered the Chinese Communist Party to liquidate itself into the KMT and submit themselves to the bourgeoisie’s leadership. This would lead to disastrous consequences for both the CCP and the Chinese working class when Chiang Kai-shek launched his bloody coup, starting in 1926.

The Japanese Communists, alongside whom Xie received most of her political education, were also mangled into a party that strictly followed the Comintern’s lines. While Xie was in Moscow, she and her classmates witnessed the resolution of the Fukumoto-Yamakawa debate. The Fukumotoists (福本イズム) were an ultra-left/boycottist tendency that had a majority in the JCP, while the Yamakawaists (山川イズム) were a minority, liquidationist faction.

The Comintern’s criticism against both of these tendencies in the form of Bukharin’s “27 Theses” was generally correct: Communists should not work in isolation from the masses, but when they work within mass organisations they should also not lose their political and organisational principles and independence. However, a healthy, Bolshevik international leadership would have striven for hosting democratic discussions with the membership of a section to argue for their perspectives. Instead, the Comintern, by now having adopted Zinovievist methods, simply declared the debate to be resolved and reorganised the JCP’s Central Committee that excluded Fukumoto who was still a popular figure within the JCP at the time.

This method of issuing orders from the top, not involving the ranks in debate, and changing leaders bureaucratically, led to the demoralisation of the most conscious party members and was part of the Stalinisation of all the communist parties around the world. Of course, Fukumoto was also charged with being a “Trotskyite”.[8] Such a bureaucratic method of enforcing political lines, coupled with the anti-Marxist theories such as “Socialism in One Country,” and popular frontism, were what Xie was given as her education rather than a genuine Bolshevik training.

Xie’s overall political education was shaped by her exposure to two big ideological struggles within the Third International: one among the Japanese Communists, as we have seen above, but the other more consequential fight between Trotsky’s Opposition and Stalinism was what shaped the thinking of the bulk of Communist Party activists around the world.

Her response to the Trotsky-Stalin struggle, was regrettably limited by her lack of access to the primary sources. She was deliberately barred from learning of Trotsky’s real arguments by the Stalinist bureaucracy. Hence, her position seemed orthodox Stalinist on the surface. However, as we shall see, the actual policies that she promoted were, time and time again, at odds with the Stalinist line.

We know she supported Stalin against Trotsky because otherwise she would not have been allowed to attain a leading position in the Third International. Her comments in her oral memoir* (transcribed while she was on her deathbed in Beijing and being persecuted during the Cultural Revolution) showed she was misinformed on a basic factual level about the “anti-Party” activities of the Left Opposition. She referred to Trotsky, as the head of the “anti-center” faction, followed by Kamenev, Zinoviev, Radek, Sokolnikov, and Bukharin. [9]

There was another barrier. Studying alongside Japanese students with only a basic knowledge of Russian, there was little chance for her to communicate with Russian-speaking supporters of Trotsky, while at this time the Chinese Left Oppositionists in the Sun Yat-sen University had barely formed.

After Xie completed her studies in Moscow, with all her strengths and limitations, she set out for Shanghai to join fellow Taiwanese Communists to prepare for a founding Congress of a new party in Shanghai.

The struggle against repression

The conditions of work for the young Communist Parties of the region were very difficult. Harsh economic conditions coupled with brutal oppression placed enormous obstacles for the work. Many were left to rot in prisons while others buckled under the pressure. At the same time, however, the repression pushed some of the strongest and most dedicated revolutionaries to the fore. In Xie’s case, she did not expect to become a leader in the TCP. The position was thrust upon her because many of her comrades abandoned the struggle in one way or the other.

In 1928, the Taiwanese Communist Party, which the Third International first instructed to be a Taiwanese national branch of the Japanese Communist Party, was founded above a photography studio in Shanghai. Present were representatives from the Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and American Communist Parties, in addition to trained Taiwanese Communists from different national sections. The founding congress elected a central committee, along with passing a number of programmatic and perspectives documents. The founding political thesis, in accordance with the Stalinist “two-stage” theory, contended that the working class in Taiwan was still too weak, and so revolutionaries should struggle to purge the remnants of feudalism from Taiwanese society and restrict themselves to democratic struggles instead of urging the working class to take on the socialist tasks. Here we see again the dominance of the Stalinist Comintern’s ideas and methods in the newfound TCP.

Initially Xie played a secondary role in the party. At the founding congress of the TCP, she was assigned the administrative work of organising International Red Aid presence in Taiwan. Only ten days after the congress, however, an underground reading group of the party was raided by KMT operatives and Japanese police (stationed in the Japanese Concession in Shanghai). Xie and others managed to avoid any charges, although they were still extradited by the Japanese to Taiwan.

The repression meant that leading members in and outside Taiwan were intimidated. A large group of the elected leadership fled Taiwan in fear of arrest, leaving Xie and two other leaders to shoulder all of the work there. For example, Cai Xiaoqian (蔡孝乾), a founding Central Committee member, left the organisation forcing Xie to take upon herself the entire burden of leading the party. Thankfully, Xie did not have to fight alone. She had loyal comrades in Lin Rigao (Lîm Ji̍t-ko, 林日高), Zhuang Chunhuo (莊春火) also Central Committee members, and new recruit Yang Kepei (楊克培).

Later in 1928, the increased repression against Communists throughout Japan exacerbated the already difficult conditions inside Taiwan. Xie, despite not being charged, was still on the watch list. Japanese police routinely raided her home and workplace, and she had to repeatedly hide documents in compromising places like the cesspit. At times she destroyed them outright to prevent the police from getting their hands on important information. Meetings and reading groups were, of course, difficult to safely convene.

The TCP’s branch in Tokyo was liquidated only four months after its founding. The JCP then sent Watanabe Masanosuke (渡辺 政之輔), chairman of the JCP Central Committee, to visit Taiwan personally with large funds and documents in hand to assist the young party, but he was discovered by the police and committed suicide in Keelung in October 1928. Without the guidance and financial assistance of the more experienced JCP, the TCP was left to its own devices in an extremely difficult condition. It had to be led by a weak Central Committee staffed by only three members, including Xie herself. Under these conditions just to hold the party together was an impressive task carried out by Xie.

But nevertheless, these stringent conditions did have an effect on the activities of the party. Even though Xie independently worked out a balanced combination of patient legal and illegal work to recruit and train new party members, it was going to take time and vigilance for the party to become more consolidated organisationally and politically. Gains would also be followed by setbacks. In early 1929 for instance, the Tenant Union, a national militant peasant organisation that the TCP gained control of, was forced to go underground due to a mass arrest of its leaders.

It is common that heavy pressure from strenuous objective conditions would also push unhealthy dynamics within the revolutionary party to the fore, and this was especially so for the TCP. Lin Rigao and Zhuang Chunhuo, the only two remaining central committee members who steadfastly built the party with Xie in the early days, would become exhausted and resign from the party.

Repression did not only lead to timid responses. It also exacerbated the impatience among the younger members and emboldened ultraleft tendencies. However, it is precisely in these times that revolutionaries must not lose their heads and embark on adventures. Unfortunately, in face of a virulent ultra-leftist faction that was backed by the Stalinist Third International, Xie did not have the means to keep the TCP to her correct approach.

Ultra-leftism vs Xie’s approach to mass work

The tactics that Xie pursued after assuming greater responsibilities demonstrated her ability to independently arrive at Bolshevik conclusions despite having been trained and led by a degenerated International. At this time, the Comintern adopted the ultra-left “Third Period” theory under Stalin’s direction, and believed that the CPs around the world would rapidly absorb the revolutionary working class if they openly set up unions and campaigns hostile to the reformist mass workers’ organisations. This tactic flatly ignored the Leninist method of “patiently explaining” to the majority of the newly politicised working class, who inevitably fall behind the reformist leaders of their mass organisations. Such a tactic only antagonised the working class and isolated the radical layer from the wider masses.

Although the Comintern’s adventurist strategy and lack of any sense of proportion also seeped into the founding organisational resolution of the TCP and many of its founding members were influenced by this, reducing the TCP to a sect from the very beginning, Xie’s thinking led her to contradict this erroneous approach. In the first period of her leadership, she placed priority on recruitment and training of cadres, instead of believing that a small handful of raw Communists could rapidly lead the masses. She also sought ways to form principled united front works with the new, large Taiwanese trade unions that were moving from reformism to militancy.

The TCP began to work within the Cultural Association which was in left-wing ferment, leveraging Xie’s previous ties with many youth and student leaders there, and gradually recruited. In this milieu Xie would score a major breakthrough in the recruitment of nationally known militant peasant Tenant Union (農民組合) leaders Jian Ji (Chien Chi, 簡吉), Zhao Gang (Tío Kang, 趙港), and many others.

Militant peasant leader, Jiang Ji, who later joined the Taiwanese Communist Party / Image: public domain

Militant peasant leader, Jiang Ji, who later joined the Taiwanese Communist Party / Image: public domain

This was a tremendous boost, as the Tenant Union had over 23,400 members all over Taiwan in 1927. Yet it was also an organisation in flux, as it only had 13 members two years prior.[10] In order to effectively transmit revolutionary ideas to the rank-and-file, it was necessary to first educate and consolidate, then recruit the leading and middle layer of natural mobilisers of the tenant union into the Party, which would not be an easy task given the watchful eyes of the Japanese colonial government.

Xie clearly understood this. Rather than immediately mobilise this mass base towards activism, her first step was to set up an officially entitled “Society of Social Science Studies” in the headquarters of the Tenant Union, where they read books like The ABCs of Communism. Xie and other TCP members also gave lectures on topics such as the international proletarian movement and “Critiques of the Tapani Incident (a failed uprising against Japanese Colonial government in 1915).” This reading group was able to meet thirteen times before it had to be moved to the International Bookstore (國際書局), which was a legal front and a space for propaganda work set up by Xie and Yang Kepei (楊克培).[11]

The work with the Tenant Union was not restricted to the education of leading organisers. The TCP took an active part in guiding the further consolidation of the Tenant Union as a national organisation, and directed its second national congress with much influence over the resolutions that were passed from behind the scenes.

Xie further viewed the Tenant Union as an avenue to reach out to broader youth and women, and incorporate them into revolutionary socialist politics. She convinced the Tenant Union leadership to adopt programs to recruit and educate village youth and women. The former would likely become future workers, while the latter were excluded by the predominantly petty-bourgeois feminist movements in Taiwan. Both of these groups needed to, and were ready to be incorporated into the forces of proletarian revolution.[12] These initiatives clearly demonstrated Xie’s long-term thinking and careful approach to building a solid foundation for a revolutionary party.

A meeting of the Taiwan Workers’ Alliance that became a part of the Taiwan People’s Party’s mass base / Image: public domain

A meeting of the Taiwan Workers’ Alliance that became a part of the Taiwan People’s Party’s mass base / Image: public domain

Given the underground nature of the TCP’s work, Xie also sought to use the Tenant Union as a basis to connect with workers’ organisations. For this goal, she convened a meeting between the Tenant Union, the Cultural Association, a number of reformist trade unions, and representatives from the Taiwan People’s Party in an effort to form a “United Front”.[13]

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP, 台灣民眾黨) was a legal liberal party founded by some Taiwanese bourgeois as a non-militant means to negotiate incremental improvements from the Japanese imperialists, but at this point in July 1928, it had experienced a split along class lines. Earlier in the year one of the founding members of the TPP, Jiang Weishui, who was politically radicalising under the pressure of class struggle, advocated that the TPP was a party for the workers and peasants. He then set up the Taiwan Workers’ Alliance (工友總聯盟), which was comprised of 29 large unions and 7,000 members.[14] This led the right-wing TPP founding leaders like Lin Xiantang and Cai Peihuo (Tshuà Puê-Hué, 蔡培火) to leave this party that they co-founded, to go on to form the Taiwan Autonomy Alliance (台灣地方自治聯盟), a right-wing bourgeois party openly opposed class struggle methods. In effect, the TPP had transformed into a worker’s political organisation through a process of radicalisation from below, although the illusions in reformism still remained.

Xie saw this as an opportunity. In the meeting she convened with the TPP and reformist unions, she proposed to jointly coordinate protests and resistance against police repression,[15] but her goal was to connect with the advanced section of the workers and demonstrate to them the superiority of Communist methods. Although in the end this United Front did not come to fruition, it showed that Xie was attempting a genuine Leninist approach to mass work.

The Comintern did not, however, endorse Xie’s thinking and strategy. The Third International would instead throw its weight behind a tendency of impatient ultra-lefts who would pursue disastrous policies.

Manoeuvres and splits in the TCP

From the beginning, there was already an opposition faction within the party that was swiftly forming around Weng Zesheng (翁澤生) operating in Shanghai. Prior to the founding of the TCP, Weng was considered a leading figure among Taiwanese Communists who worked inside the CCP. Although Xie was also recruited by the CCP at first, she was quickly sent to Shanghai and then Moscow for her training, and thus did not have a ring of longtime supporters in the CCP like Weng did.

Weng was also a student of onetime CCP acting General Secretary Qu Qiubai (瞿秋白); the latter would use his authority to personally intervene in future TCP affairs in favour of Weng. Being in Shanghai and in close touch with the Third International’s Far East Bureau under Pavel Mif, Weng eventually became the chief liaison between the TCP and the Comintern. He then began to use this position to present edited versions of reports from Taiwan to the Far East Bureau, and issued his own orders to the party in Taiwan on behalf of the Comintern.[16]

Weng and his clique began to criticise Xie’s leadership from the perspective of ultra-leftism and adventurism, which despite being alien to Bolshevism were in line with the Stalinist leadership internationally at that time. Their critique against Xie is best summarised by a “missive” from the JCP to Taiwan which researcher Anna Belogurova showed was likely to be authored by the Weng faction in reality, and included charges such as:

“Separation from the masses as the consequence of the lack of workers and peasants in the Party (as well the lack of effort made to involve them) and their lack of awareness of the Party’s existence; the opportunism of the Communist Party and the vacillation of its intellectuals after their arrests; setting the wrong goals for the creation of a mass legal toilers’ party; lack of cells and a party newspaper; and inadequate leadership of the peasant movement through an intellectuals’ study society.”[17]

Note that by 1930, the TCP only had 25 members on the books.[18] To immediately expect the masses to have “an awareness of the Party’s existence” and rapidly recruit is utterly ignorant of the necessity for cautious underground work. The criticism on “inadequate leadership of the peasant movement” rather revealed that Weng expected the TCP to be leading massive struggles right away, instead of doing the necessary work of cadre consolidation.

Nevertheless, a mood of impatience within the ranks of the TCP led many to side with Weng. Aside from being able to win over peasant leader Zhao Gang, Weng also gained Su Xin who was a new arrival from Japan and immediately became dissatisfied with Xie’s leadership. This coincided with the demoralisation of Xie’s allies, which was exacerbated by Xie’s bellicose temperament.[19] When Lin Rigao and Zhuang Chunhuo resigned from the party, Xie would have to face the opposition as the only remaining Central Committee member.[20]

Xie initially sought to remedy the collapse of the CC by convening a Conference in Songshan, but it was here that the opposition faction reared its head. The Weng faction presented their views directly to her, including the need to accelerate Red Union work, the need to liquidate the Cultural Association so that the TCP could more directly and publicly recruit, and their grievance over her leadership. She conceded on some of her mistakes, but maintained her disagreement with the adventurist line that the Weng faction was proposing.[21]

After the Songshan Conference, Weng continued to manoeuvre against Xie under the banner of Stalinist orthodoxy. On top of the repeated complaints Weng had made to the Comintern about the TCP, Weng got Qu Qiubai to make a number of criticisms against the TCP, and recommended it to revise the party programme and “fight against right opportunism”. Weng and his group then presented these critiques as directives from the Third International. They then accordingly formed a faction called the “Reform Alliance (改革同盟)” after the Songshan Conference and elected its own Central Committee.[22]

Xie was not only reduced to a minority, her perspectives contradicted that of the Comintern’s line which was embraced by the Reform Alliance. Weng eventually secured the backing of the Far East Bureau. His clique then held a “Congress” without inviting Xie’s faction, and declared Xie and two of her followers expelled from the TCP in 1931.

Stalinism in practice and the fall of the TCP

Xie’s methodical approach to cadre building and united front work was thrown out of the window after her expulsion. In its stead was a turn to open adventurism and a bid for a Red Union, to which the Weng clique thought they could rapidly rally all of the Taiwanese workers.

At the same time, economic crisis and severe wage cuts and unemployment, as well as a spontaneous, albeit heroic, armed uprising of the indigenous Seediq people in 1931, known as Wushe Uprising (霧社事件), enhanced their illusion that a time for insurrection was imminent, and that a small group would be able to lead it.

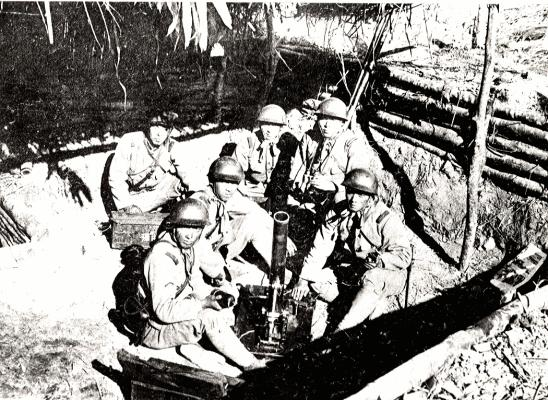

Japanese soldiers brutally bombarding the Seediq people during the Wushe Uprising / Image: 王仲立 public domain

Japanese soldiers brutally bombarding the Seediq people during the Wushe Uprising / Image: 王仲立 public domain

Nonetheless, Marxists understand that even in the most favourable social conditions, the role of the revolutionary party is never to substitute itself for the masses. Instead it must go through all the necessary experiences with the masses as they struggle, and patiently explain the need to adopt a revolutionary program to win them over voluntarily.

In truly Stalinist fashion, the new TCP leadership expelled rank and file members of the party and of the front organisations who opposed the open turn, or did not understand the sudden strategic change. Dissenters were branded as “Trotskyists” and driven out, even though Trotsky was an obscure figure in Taiwan.

One small strike after another were carried out under the TCP’s direction with mixed results. At times the TCP even tried to mold a spontaneous small strike into a campaign against the Taiwan People’s Party, contrary to the striking workers’ wishes.[23] In this process the TCP gained not the following of the masses, but the attention of the Japanese police.

Finally, in 1931, the Japanese government initiated a mass arrest against any suspected TCP members. Thanks to the ample amount of information they had gathered, all of the top leadership of the TCP were tracked down and arrested, including Xie and her followers. The Japanese government at the same time struck out against the entire Taiwanese Left. The Taiwan People’s Party, along with all peasant Tenant Unions were shut down and outlawed.

The new members recruited from the TCP’s open turn were being promised a glorious uprising that was just around the corner. This illusion led to even more adventurist tactics. In reaction to the arrest of their leaders, a handful of young party members planned an insurrection based on a group of 40 peasants in Dahu (大湖) and Zhunan (竹南). They were arrested before the plot was even carried out.[24]

These developments ushered in a long period of demoralisation in Taiwanese society that spanned for more than a decade, and all militant movements would cease until the end of WWII.

Given the tremendous amount of sacrifice and hard work put in by the Taiwanese Communists, it was a tragedy that the TCP suffered such an ignominious end. In the final analysis, only the correct banner, method, and tradition of Bolshevism could have led a small party to build up and play an enormous role in leading the working class to take power. Without this, endeavours in even the most favourable circumstances would end in failure, as seen in countless examples from all over the world.

The iron determination in fighting against oppression and abolishing the old world that all the members of the TCP had is a revolutionary heritage that Taiwanese and international Marxists defend. But we are also duty bound to learn and absorb the lessons that they paid with their lives to learn.

Notes

[1] 翁佳音編,《台灣社會運動史》-勞工運動,右派運動,稻鄉出版社,台北,1992, p.15

[2] 連溫卿,《台灣政治運動史》,稻鄉出版社,台北,2003, p.50

[3] 謝雪紅口述,楊克煌筆錄,《我的半生記》,楊翠華,國家圖書館出版,台北,2004,p.23

[4] John Peter Roberts, China: From Permanent Revolution to Counter Revolution, Wellred Books, London, 2016, p.31

[5] 謝雪紅, p.229

[6] John Peter Roberts, p.65

[7] 林瓊華,《從遺忘到現在:謝雪紅的歷史在台灣與中國的影響與遺緒》,台灣史學雜誌,第15期,2013年12月,p.4

[8] 謝雪紅,p.247

[9] Shih-shan Tsai, The Peasant Movement and Land Reform in Taiwan, 1924-1951, Chinese edition, Taipei, 2017, p.192

[10] 陳芳明,《謝雪紅評傳》,城邦文化出版,台北,2009, p.73

[11] Ibid, p.78

[12] 翁佳音編,《台灣社會運動史》-勞工運動,右派運動,稻鄉出版社,台北,1992, p.72

[13] 陳芳明,p76-77

[14] 警察沿革誌出版委員會,《台灣社會運動史(1913-1936)》,創造出版社,台北,1989

[15] Anna Belogurova, “The Civic World of International Communism: Taiwanese communists and the Comintern (1921–1931)”. Modern Asian Studies, Available on CJO doi:10.1017/S0026749X12000327, p.16

[16] Ibid, p.15

[17] Ibid, p.17

[18] 林瓊華,p.14

[20] 楊克煌,《我的回憶》,楊翠華,國家圖書館出版,台北,2005,p.82-83

[21] 陳芳明,p.128-130

[22] Belogurova, p.19

[23] 翁佳音, p.192-p202

[24] 盧修一,《日據時代台灣共產黨史(1928-1932)》,前衛出版史,台北,1990,p136