On Friday 3 September, Japan’s Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga announced that he would not be running in the leadership contest of his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) scheduled for later this month. This effectively means that he will be stepping down as Prime Minister after barely a year in office. However, given the general crisis of Japanese capitalism, what we are seeing here isn’t just the end of Suga’s own political career, but the end of relative political stability that the ruling class has managed to maintain for the past decade. In Japan, a new, turbulent epoch of political instability is being ushered in.

Dead man walking

Yoshihide Suga came into the public spotlight as a close associate of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. He won the leadership race last year as a continuity candidate, promising to maintain the status quo of political stability that Abe managed had overseen in his eight years in office.

Abe managed to maintain the unchallenged dominance of the LDP in Japan through measures he would brand as “Abenomics”. These measures were a mixture of austerity, deficit spending, and quantitative easing that aimed to boost Japan’s inflation rate. Despite Abe’s claims, these measures did not “revive” Japan’s economy. While large corporations and the rich benefited tremendously under Abe, Japan’s economy remains stagnant. Still, there were no major collapses or crises during Abe’s administration, and he has taken credit for maintaining this superficial stability.

Yet Suga’s year in office was anything but stable. Under his watch, the COVID-19 pandemic was handled catastrophically, with the country now going through its fifth wave of infections (16,729 per day) despite having instituted multiple lockdowns. Only 49% of Japan’s population has received the first dose of vaccine at the time of writing. Over the course of 2020, the economy shrank by 4.7% and even more sharply, by 5.1%, in the first quarter of this year. Conditions of life under lockdown have led to a sharp rise in suicide rates, mostly among women, children, and adolescents.

Amidst the suffocating pandemic measures, Suga also rammed through a number of deeply unpopular measures. Among many other things, he insisted on dumping the irradiated waste water from the Fukushima nuclear plant straight into the ocean. But most despised of all has been Suga’s insistence on going ahead with the Olympic games despite opposition from 83% of the Japanese people.

Given all of the above, and compounding this with a corruption scandal that involves Suga’s own son, support for Suga and the ruling LDP government has plummeted. The political discontent against this regime was already apparent before the Olympics, when Suga’s support dropped to 32.2% and the LDP failed to win the Tokyo metropolitan assembly elections in July. After the Olympics Suga’s popularity dipped to 28%. The LDP then suffered a massive defeat in the mayoral elections in Yokohama, the second-most populous city in Japan, and Suga’s own parliamentary constituency.

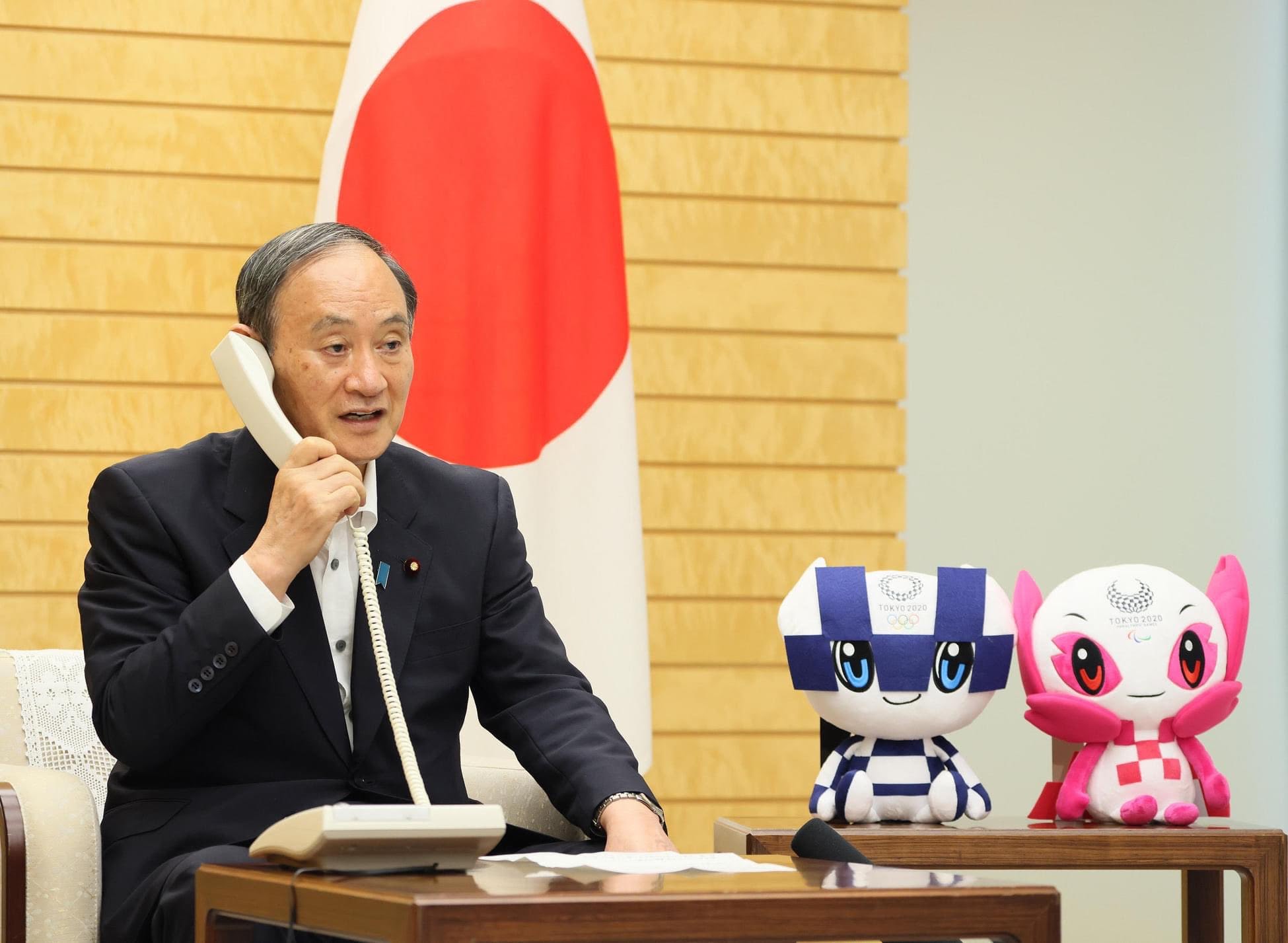

Suga insisted on hosting the Olympics in the middle of the pandemic despite widespread opposition / Image: @hangorinnokai, Twitter

Suga insisted on hosting the Olympics in the middle of the pandemic despite widespread opposition / Image: @hangorinnokai, Twitter

By this point, the writing was on the wall for Suga. There is no way that the LDP can maintain its parliamentary majority at this November’s general election as long as he is in leadership. As such, various factions within the LDP began to plot their own moves against him.

Fumio Kishida, an ambitious leader of the Kochikai faction, made the first move. On 28 August, Kishida suddenly called for term limits to be established for the LDP’s top leadership. In effect, this was a shot at the LDP Secretary-General and Suga’s second in command, Toshihiro Nikai, who has held this position for over five years. Kishida’s call rallied the second and third rank politicians in the ranks of the LDP who were dissatisfied with Suga and Nikai’s leadership. At the same time, powerful grandees like Shinzo Abe and current Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso began distancing themselves from Suga. Suga’s isolation became evident to everyone.

In a desperate bid to save himself, Suga clumsily tried to maneuver. He attempted a major overhaul of the LDP’s top leadership and even considered dissolving parliament to buy himself time. Unfortunately for him, it was already too late. By early September, Suga was completely suspended in midair. Finally facing up to reality, Suga announced his decision to step down.

The final days of Suga’s tenure played out like a well-produced political crime drama. The fact is, he had been a dead man walking since the first day he stepped into office. Suga inherited a poisoned chalice from Abe: a country inundated with a permanently stagnant economy and various social crises. The pandemic had arrived in Japan before Suga had even taken charge, with such episodes as the Diamond Princess cruise ship outbreak. The slowness of Japan’s response to the first wave of local infections was caused in large part by the fact that, unbelievably, doctors were required to use fax machines to report COVID cases. This is not so much a sign of technological backwardness – Japan is anything but technologically backward – rather, it was a result of a thousand and one bureaucratic obstacles in Japan’s healthcare system.

Even if Suga hadn’t been a bumbling bureaucrat all along, which he most certainly is, he would nevertheless have found himself entangled in crises which he would have been powerless to prevent slipping out of control. This is because the crisis of the senile, decaying system of Japanese capitalism is now rapidly unraveling, and no amount of skillful statesmanship can mask its morbid symptoms.

Not just Suga

Now that Suga is out, all the big players in the LDP are making their move to fill the power vacuum. Among many others, Fumio Kishida has already thrown his hat into the ring. Current vaccine tsar, Taro Kono, is said to be the front runner for the LDP leadership. Shinzo Abe has endorsed former Minister for Internal Affairs and Communications Sanae Takaichi as the new candidate for the torch-carrier of “Abenomics”.

Unfortunately for any of these people, the victory of the LDP in November’s general election is far from assured, even if Suga is out of the picture by then. A poll conducted by Mainichi Shimbun in late August indicated that while the LDP is still ahead of other parties at 26%, its support has dropped. Not only that, the vast majority of respondents (42%) still say they support no political party. As such, if the turnout in the November general election is low, the LDP has perhaps its best chance of remaining in power. But should there be a high turnout of voters who want to punish the LDP for its corruption, incompetence and greed, as was the case for the Yokohama mayoral election, then the LDP could very well lose.

Whether the LDP wins or loses the upcoming general election does not alter the fundamental process that is taking place. The epoch of relative political stability in Japan is over. The governments to come in Japan will not enjoy the stability and long life of those that have gone before. The contradictions of Japanese capitalism are now expressing themselves in more explosive ways, and the measures of the past are no longer sufficient to taper their effects.

The meaning of the crisis of the LDP

The upcoming era of social and political instability in Japan, flowing as it does from the economic crisis of Japanese and world capitalism, will shake up the country, and with it much of the world. This is because of the integral role that Japan still plays in the world capitalist system, and particularly in the balance of forces in the Pacific region.

Japan remains the third biggest economy in the world and home to some of the largest private banks and other companies in Asia. It is also a key ally of Western imperialism not only in Asia but also as a member of imperialist organisations such as the G7. Japanese capital is also deeply intertwined with that of the West, thus making it an organic component of the US-led imperialist effort to contain growing new powers such as China.

In this capacity, the Japanese ruling class’ interests have been primarily stewarded by the Japanese state which the LDP has controlled for the vast majority of the time since WWII. Of the 63 years since Japan’s first post-war election, the LDP has governed for 59 of them. This means that the LDP is deeply intertwined with the Japanese bourgeois state itself. The crisis of the LDP is the crisis of the capitalist state in Japan.

At its roots, the LDP is a political alliance consisting of the big bourgeoisie, regional clientele networks, right-wing petty bourgeois nationalists, and yakuza criminals. This conservative coalition has been the preferred political weapon of the Japanese ruling class. Despite its ironic name (the “Liberal Democratic Party” is neither liberal nor democratic), the influence of liberals has been pushed to the margins.

On the other hand, the main force based in the working-class in opposition to the LDP was historically the Socialist Party, which had a mass following and was rooted in the trade unions. Yet over the years, the reformism of this party led it to make one mistake and betrayal after another, in the process reducing itself to a rump. The lessons of the post-war left in Japan are beyond the scope of this article. The main point here is that the LDP’s longevity largely owes itself to the fact that it has faced no serious opposition.

The divisions opening up in the ruling class, which will find itself unable to govern in the way that it once did, are the product of building underlying contradictions. For Japan, the infighting within the LDP represents a split in the Japanese ruling class. The seven major factions within the LDP are in a state of severe disunity. No matter who wins out to become the new party leader at the end of September, their term in office will not be that of a ‘consensus leader’ in the manner that Abe was in the past. Intrigues and splits will continue to ravage the LDP.

The LDP is a coalition of the most reactionary elements in Japanese society, including the Yakuza / Image: elmimmo, Flickr

The LDP is a coalition of the most reactionary elements in Japanese society, including the Yakuza / Image: elmimmo, Flickr

A divided LDP means that the Japanese ruling class can no longer enforce its agenda with the consistency it requires. What will they have to lean on going forward to implement their rule? Either a chaotic LDP or potentially a hodgepodge of smaller parties in coalition. This means that the next government would be just as inconsistent and disruptive as that of Suga, if not more so.

Internationally, an unstable Japanese government would create serious problems for Western imperialism. Japan’s cooperation with the West, especially the US, has long been taken for granted. Political instability is now turning Japan from a constant into a variable quantity in the calculations of US imperialism, particularly in its efforts against China. Suga already demonstrated great reluctance this year in confronting China alongside the US over the issue of Taiwan. Succeeding governments in Japan are unlikely to be as reliable for the US as they once were.

What’s next?

Underneath the political turmoil in Japan today is a society in profound crisis. “Abenomics” is no longer effective in masking the reality of Japan’s suffocatingly stagnant economy. The ruling class is hopelessly looking for a new measure to get out of this impasse, which paved the way for the split that we are now witnessing.

At the same time, there is a burning desire for a genuine political alternative among the Japanese masses. As the aforementioned poll shows, the most “popular” political party in Japan is “no party.” Notably, the LDP is not the only party losing support. All major and minor parties have seen their support decline in the same period, including the Japanese Communist Party (JCP). This shows that there is a deep distrust towards the entire Japanese political establishment, and sooner or later this distrust will express itself in some form.

The profound distrust towards all politicians and the anger against the system is summed up in remarks by a working student in Tokyo, who said:

“It is as if they [politicians] are living in a different world, and are completely ignorant of the lives of us ordinary people with low incomes. The high taxes levied upon normal people go into their pockets, and this makes me furious… Japan's economic bubble has burst, and our politicians are all old-farts who are set in their ways and working against the times.”

Unfortunately, at present there is no genuine alternative for the working class that can channel this anger into a powerful movement capable of transforming society. Although the LDP is severely weakened, no opposition party has the level of support required to single-handedly replace it. The bourgeois-liberal Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ) is currently the biggest opposition party, but it would have to secure a coalition with all other opposition parties in order to run a credible ‘anti-LDP’ platform. What this platform would look like concretely and how the Japanese masses will perceive it remains to be seen.

Nonetheless, it is a foregone conclusion that whatever coalition the CDPJ might manage to cobble together to get into government, it will not be able to contain the general pressure caused by the crises in society, which in the final analysis cannot be resolved under capitalism.

Japan is therefore entering into a new era of political instability and dysfunctional governments. Coupled with the deep yearning for genuine change, this could open up fissures through which new movements and struggles may erupt in a manner that the country has not seen for decades.

Japan has long been regarded – not without reason – as an exceptionally stable country. But the appearance of stability has merely masked building contradictions that have developed over decades of stagnation, and more recently of sharp decline. The country has now reached a turning point, politically expressed in the acute crisis of the LDP. In the turbulent period that opens up, the world will bear witness to the intense class contradictions that have built up in Japanese society, and the working class will be forced into more and more open conflict with the whole Japanese ruling class. The Japanese masses are on course to join their class brothers and sisters around the world in the struggle against capitalism. This struggle will pose in the minds of the most class-conscious Japanese workers and youth the need for the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism under a leadership armed with clear Marxist ideas and an internationalist perspective. We at the International Marxist Tendency are working to build such a leadership all over the world, and we eagerly invite revolutionary workers and youth in Japan to join us.