This article was first published in German by the comrades of Der Funke, the IMT in Austria. Here we provide an English translation on this important question of Queer Theory. Is it compatible with Marxism? Can there be such a thing as “Queer Marxism”? Yola Kipcak in Vienna replies in the negative, and explains why.

Oppression and discrimination are integral parts of the dominant system under which we live, which includes the systematic persecution and stigmatisation of sexualities and identities that don’t conform to the ‘norm’. As Marxists, we fight determinedly against any form of sexism, discrimination and oppression. However, we also have to seriously look into the question of how to overcome the present barbaric conditions and how to guarantee the free expression of all humans, which involves looking into theories and methods of achieving these goals.

In this article we will deal with a particular strand of feminist/gay theory that gained popularity particularly in the 1990s. It has since gained some influence, especially at universities, but also among some sections of workers’ organisations that have adopted “Queer ideas”. We therefore take a close look at what lies behind so-called Queer Theory and what the Marxist stance towards it should be.

What is Queer Theory?

Queer Theory emerged mainly in the United States in the 1990s among academic circles, particularly those occupied with Gay Studies, and in connection with gay activism around the HIV/Aids crisis. Originally an insulting term for homosexuals, “queer” was taken up and given a positive twist by the gay movement. Queer Theory uses this term and deals with what they see as ruptures in the connection between biological sex, gender-identity, and sexual desire – for example transgender, homo-/bisexuality, fetishes, etc. – in short, identities or dispositions that are seen as “diverging from the norm”.

Queer Theory centres on the question of individual identity, in particular sexual identity, gender and sexual orientation. Sexuality is seen as crucial for understanding the whole of society. Queer literature critic, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, goes as far as to write: “[A]n understanding of virtually any aspect of modern Western culture must be, not merely incomplete, but damaged in its central substance to the degree that it does not incorporate a critical analysis of modern homo/heterosexual definition.” (Epistemology of the Closet, p. 1.) In its own words, Queer Theory explores “how sexuality is being regulated and how sexuality influences and structures other social areas such as state policies and cultural forms. Its main concern is to deprive sexuality of its seeming naturalness and to make it visible as a cultural product entirely permeated by relations of power.” (Jagose, p. 11, translated from the German.)

However, Queer Theory is not an actual unified and coherent theory, as it is deliberately kept extremely vague and “diverse”, and does not claim to have common definitions. This has the handy side-effect of silencing any criticism with the argument that “I, for one, see this in a completely different way” – which Annamarie Jagose, a feminist academic who wrote a renowned introductory book to Queer Theory, admits herself. About the term “queer” she writes: “Its vagueness protects queer from criticism such as the accusation of exclusionary tendencies of ‘lesbian’ and ‘gay’ as identity categories.” (Jagose, p. 100.)

Yet it would be wrong to assume that there is no common ground in the views of Queer Theory advocates. Queer Theory builds upon certain philosophical premises that necessarily lead to a certain understanding of the world in which we live and whether/how we can change it.

The main premises of Queer Theory, which we will examine more closely below, are the following: our (gender) identity is nothing but a fiction. Hence, hetero-and homosexuality is also a cultural fiction. This fiction is produced by discourses and power in society. We must uncover how these discourses function and parody them (ridicule them, show their contradictions, “displace” them).

Identity crisis

It is not by accident that Queer Theory rose to popularity in the 1990s. Two decades earlier, around the eventful year of 1968 and thereafter, the world saw many revolutionary movements such as the May 1968 general strike in France, the 1969 “Hot Autumn” in Italy, the 1968 Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia, the Civil Rights Movement in several countries and many more.

With the new wave of class struggle, the women’s movement also experienced a renewed upsurge. Without doubt many of the radical, feminist and gay groups that emerged at that time viewed themselves as socialist, or at least connected to the class struggle. For instance, the Group of Independent Women (AUF), founded in 1972 in Austria, declared in the first issue of their paper: “The women's movement paves the way for a sexual and cultural revolution. However, this can only be seen in connection with an economic revolution." (AUF, Eine Frauenzeitschrift, Number 1, 1974)

Simone de Beauvoir’s remark: “One is not born, but rather becomes, woman" is a precedent for Queer Theory / Image: Flickr, Kristine

Simone de Beauvoir’s remark: “One is not born, but rather becomes, woman" is a precedent for Queer Theory / Image: Flickr, Kristine

However, after the betrayals of those revolutionary movements and strike waves, the perspective of a revolution carried out by the working class began to be seen as far-fetched or impossible to many demoralised left activists. Without the connecting element of mass social struggles that united the working class, the end of the 1970s saw the women’s and gay movement drift off into identity politics and veer away from radical or revolutionary aspirations towards small, local circles. Their activism was now centred on the exchange of experiences, culture and art projects and about the administration of past achievements such as women’s shelters and emergency hotlines. The gradual institutionalisation of the women’s movement on a state level – within the reformist parties, through the creation of women’s ministries and through professorships and scholarships at universities – led to a strengthening of petty-bourgeois ideas within the women’s movement of the late 1970s and 1980s.

Feminist theories that portray class struggle as secondary to the cultural struggle against patriarchy, or that deny the existence of class struggle altogether, gained influence. It was no longer about fighting against class society and women’s oppression rooted within it, but about fighting against “transhistorical patriarchy” (i.e. remaining the same throughout different forms of society). The revolutionary subject was no longer the working class but woman oppressed by man. From this premise an abundance of texts and discussions were launched that dealt with the question of the essence of patriarchy and how “woman”, who had become the main subject of analysis, could be defined. The idea of differentiating between biological sex and social, acquired gender became prominent. It is expressed in Simone de Beauvoir’s emblematic remark:

“One is not born, but rather becomes, woman. No biological, psychical or economic destiny defines the figure that the human female takes on in society; it is civilization as a whole that elaborates this intermediary product between the male and the eunuch that is called feminine. Only the mediation of another can constitute an individual as an Other.” (The Second Sex, p. 330.)

Here, we already see the roots of what will later become central ideas of Queer Theory: 1) the “Woman” as such does not exist. 2) She is only shaped and brought up to become one by society.

But if “woman” (which shall no longer be narrowly defined by biology) doesn’t exist – who is this subject that is meant to fight for its emancipation? The search for the true identity of woman, for the new revolutionary subject, occupied the professors and writers of that time. In their quest for the “female essence”, some discovered the burning of witches and viewed shamanism and witchery as an oppressed manifestation of femininity. Others saw “womanness” hidden within the realms of irrationality of emotion or poetry; still others found that only lesbians could truly fight for women’s emancipation as they refuse heteronormative relationships with men, and so on. Now, the question was posed as to who should have the right to represent women? Thus, during a period of declining class struggle, identity politics sank ever deeper into a crisis.

This crisis was further exacerbated by the dissolution of the Soviet Union. For many, the belief that an alternative to capitalism was possible, vanished. The malicious glee of the bourgeoisie, proclaiming the “end of history”, was mirrored in a mood of depression that gripped the left, in conditions where the forces of Marxism were too weak to present a visible alternative.

It was in this context that the ideas of postmodernism – which rejects complex systems and general processes, denies the existence of objective reality and instead builds upon small, subjective narratives – gained popularity. One of their common characteristics is the extraordinary importance the postmodernists attribute to language. “Who says that there is such a thing as reality beyond language? Language is reality!” this is the motto of these postmodern professors who win professorships, university positions and book contracts with their intellectual acrobatics. Queer Theory, whose main influences include Foucault’s Poststructuralism, Lacan’s Psychoanalysis and Derrida’s Deconstructivism, is among these ideas.

The best-known book ascribed to Queer Theory is Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990) by Judith Butler. Born in 1956, a philosophy professor with a focus on comparative literature, Judith Butler matches the typical social milieu and theoretical background of Queer Theory. In the very first sentences, she contextualises her book within the crisis of identity politics:

“For the most part, feminist theory has assumed that there is some existing identity, understood through the category of women, who not only initiates feminist interests and goals within discourse, but constitutes the subject for whom political representation is pursued." However: "[T]here is very little agreement after all on what it is that constitutes, or ought to constitute, the category of women." (Gender Trouble [GT], p. 3-4.)

The focal point of Queer Theory is the individual, the subject that has been plunged into crisis. Its identity is uncertain and contradictory, just as the world in which it lives – it is caught in a web of power relations and oppression. These core elements of Queer Theory seemed to finally give voice to what so many people felt: the permanent stress of trying to meet the demands of the system. One should be hard-working, productive, a good and strong man, a good and understanding mother and career woman, healthy in body and mind and always reaching for the stars. The alienation from oneself and the feeling of being alone in a world in which every expression of self barely seems like a caricature was finally being shouted out loud. The question was posed of who one can even be if one exists only minted and pressed by society, just like a coin with an exchange value.

This psychology of individualisation and of a vague need for resistance in the absence of a mass movement were important elements of the 1990s and 2000s. What makes Queer Theory attractive to some is perhaps the fact that it provides a language that validates the subject, that builds upon the unique point of view of oneself and that describes one’s consciousness.

The philosophical basis of the gender question

Queer Theory’s as well as Judith Butler’s main argument is that the problem of identity politics lies in its quest to search for a “true identity” of woman. After all, every woman is unique and different, and how can we determine an ever-valid definition of “woman” that hasn’t already been distorted and influenced by prejudices in society? Every representation of “woman” is therefore incomplete and excludes some women. “Woman”, says Butler, does not exist – she is nothing but a projection of prejudices and opinions on human bodies. There is no woman before she has been made into one by the power structures in society. However, as we will see later, Queer Theory does not in any way see its task as understanding what it calls “power structures”, much less breaking them.

Here, it is necessary to go on a philosophical excursion and examine how Butler reaches her argument that “woman” (or rather “genders”) do not exist, and what lies behind this argument. Because in the history of philosophy, her assertions are neither new, nor original. The only difference is that she applies old philosophical patterns exclusively to the gender question. In fact, Marxists thoroughly answered more than 100 years ago the same arguments that are being rehashed today by Queer Theory. In particular, Lenin’s excellent work Materialism and Empirio-criticism reads like a specific rebuttal of Queer Theory.

As point of departure for her argumentation, Butler takes the Dualism between biological sex and social gender described above, which she criticises. This Dualism in fact represents the relationship between matter and idea. What is the origin of “woman” – is it nature, biology, the fact that she can bear children, or is it the cultural notion of femininity – and what is the relation between these two aspects?

Behind this issue of biological sex and gender roles lies the question of which philosophical foundation we build our worldview on, idealism or materialism – since Queer Theory views the world, first and foremost, through the lens of the gender question. Friedrich Engels described the two opposing philosophical approaches in the following way:

“[W]hich is primary, spirit or nature — that question, in relation to the church, was sharpened into this: Did God create the world or has the world been in existence eternally?The answers which the philosophers gave to this question split them into two great camps. Those who asserted the primacy of spirit to nature and, therefore, in the last instance, assumed world creation in some form or other — and among the philosophers, Hegel, for example, this creation often becomes still more intricate and impossible than in Christianity — comprised the camp of idealism. The others, who regarded nature as primary, belong to the various schools of materialism.” (Engels, Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy)

The question of the philosophical foundation of any theory is far from pedantic. Depending on whether we see ideas or matter as fundamental to the world, the answer to how or whether the world can be fundamentally changed is different. Can we eradicate women’s oppression with ideas (i.e. with language, education) or through material changes (with class struggle, by changing the way we produce)?

Ultimately, no one can evade the choice between idealism and materialism. That doesn’t mean that many philosophers haven’t tried to do just that. In his book Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy, Engels refers to what he defines as “agnostics” who stand apart from idealists and materialists. He is referring to those who try to evade the question of whether thought or matter is primary by treating them as two separate spheres.

This agnosticism reached its highest form with Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), who assumed that the material reality does exist (he called it the thing-in-itself) but that this reality can’t truly be known, because by default we would impose our preconceived categories onto the world and thus “interpret” it without being able to determine whether our interpretation is actually accurate. The Dualism of sex and gender is precisely such an agnosticism: a woman’s body is one thing, the cultural prejudices about women a completely different thing. The relation between these two aspects thus becomes mysterious and unknown.

But even the genius Kant couldn’t avoid the question of whether thought or nature is primary. If humans perceive the world through their categories and senses, where do these categories with which we think come from? Do the human brain and science deduce them from nature, or do they originate from an immaterial, spiritual world, in other words, from a God? Kant himself answers this question with the latter and, though he was a genius of a scientist and philosopher, he was nevertheless an idealist.

By contrast, Marxism stands on the side of materialism: matter is primary; our ideas are functions of our brain, our senses are the connection of our (material) bodies to the material world, our culture is an expression of humans in their interaction with nature, of which they are a part.

“The materialist elimination of the ‘dualism of mind and body’ (i.e., materialist monism) consists in the assertion that the mind does not exist independently of the body, that mind is secondary, a function of the brain, a reflection of the external world. The idealist elimination of the ‘dualism of mind and body’ (i.e., idealist monism) consists in the assertion that mind is not a function of the body, that, consequently, mind is primary, that the ‘environment’ and the ‘self’ exist only in an inseparable connection of one and the same ‘complexes of elements.’ Apart from these two diametrically opposed methods of eliminating ‘the dualism of mind and body,’ there can be no third method, unless it be eclecticism, which is a senseless jumble of materialism and idealism.” (Lenin: Materialism and Empirio-criticism, chapter 1, section 5, Does Man Think With The Help of the Brain?)

Subjective idealism

Regarding the question of idealism vs. materialism, Queer Theory is not neutral. It takes decidedly one side – the side of idealism. Butler writes:

“Lévi-Strauss's structuralist anthropology, including the problematic nature/culture distinction, has been appropriated by some feminist theorists to support and elucidate the sex/gender distinction: the position that there is a natural or biological female who is subsequently transformed into a socially subordinate 'woman,' with the consequence that 'sex' is to nature or 'the raw' as gender is to culture or 'the cooked'." (GT, p.47.)

She wants to dissolve this problematic distinction between sex and gender, get rid of the Dualism, namely by declaring biological sex a cultural construct.

“Are the ostensibly natural facts of sex discursively produced by various scientific discourses in the service of other political and social interests? If the immutable character of sex is contested, perhaps this construct called 'sex' is as culturally constructed as gender; indeed, perhaps it was always already gender, with the consequence that the distinction between sex and gender turns out to be no distinction at all.” (GT, p. 10-11).

Thus sexes are not real – we are simply led on by the dominating discourse! Through regular repetitions and by acting as a certain sex, we perform sexes that are thus incorporated. That’s why our human bodies are neither male nor female (or something else), they are a complete unknown, something that cannot exist independently of our ideas about them. Even the thought that they could exist independently from our culture is unacceptable:

“Any theory of the culturally constructed body, however, ought to question 'the body' as a construct of suspect generality when it is figured as passive and prior to discourse." (GT, p. 164.)

Defending Judith Butler, some people on the left say that she does not actually deny the existence of sexes and to insinuate otherwise is a malicious exaggeration of her ideas. This is true only insofar as she understands biology also as language, as a cultural attribute. For all her inaccessible writing style she is relatively consistent in the defence of her idealistic views:

"The presumption here is that the 'being' of gender is an effect, an object of a genealogical investigation that maps out the political parameters of its construction in the mode of ontology. To claim that gender is constructed is not to assert its illusoriness or artificiality, where those terms are understood to reside within a binary that counterposes the 'real' and the 'authentic' as oppositional."

Her inquiry "seeks to understand the discursive production of the plausibility of that binary relation and to suggest that certain cultural configurations of gender take the place of 'the real' and consolidate and augment their hegemony through that felicitous self-naturalization.” (GT, p. 43.)

Judith Butler's Queer Theory explicitly takes the side of philosophical idealism by reducing sex and gender to cultural constructs / Image: Miquel Taverna

Judith Butler's Queer Theory explicitly takes the side of philosophical idealism by reducing sex and gender to cultural constructs / Image: Miquel Taverna

If we translate this pompous formulation into comprehensible English, Butler tells us that every form of Being is simply an effect of ‘discourses’ (language), that is to say: Idea, the word, language is primary, matter an effect derived from it, ultimately also only language. This means that, for her, anatomy, biology and the natural sciences are all language constructs. That’s why sexes are not “artificial” – because from her point of view there is nothing outside of cultural constructs. To think of material reality as something that exists independently from our ideas only means to be hoodwinked by the ruling discourse, which tells us that there is such a thing as a Dualism between “matter” and “culture”. This ruling opinion (“hegemony”) makes us believe that there is a “real” sex and an “unreal” gender. But Butler has seen through it all! ALL is culture, all is language – all is Idea!

"The 'real' and the 'sexually factic' are phantasmatic constructions – illusions of substance – that bodies are compelled to approximate, but never can”, says Butler. “[...T]his failure to become 'real' and to embody 'the natural' is, I would argue, a constitutive failure of all gender enactments for the very reason that these ontological locales are fundamentally uninhabitable." (Gender Trouble, p. 186.)

This idealism is not a peculiarity of Judith Butler with whom we have dealt so far. It is a founding pillar of Queer Theory, which is that men, women, but also sexual orientation are cultural constructs. Thus Queer-texts often like to put nature, biology, sex, man, woman, etc. in inverted commas to demonstrate that the authors no longer fall for the trick that the real world exists. Just to give a few examples:

Annamarie Jagose argues: “By pointing out the impossibility of a ‘natural’ sexuality, queer questions seemingly stable categories such as ‘man’ and ‘woman’” (Jagose, p. 15.).

David Halperin: “To be socialized in a sexual culture means just that: the conventions of this system gain the status of a self-fulfilling inner truth of ‘nature’” (quoted in Jagose, p. 31, translated from the German).

Gayle S. Rubin: “[M]y position on the relationship between biology and sexuality is a ‘Kantianism without transcendental libido’.” (read: a Kant that doesn’t trespass [‘transcend’] beyond the realm of immediate experience to the real body, ergo a Dualism that eliminates matter = pure idealism) (Thinking Sex, p. 149.).

Chris Weedon writes about her philosophical foundation that “language, far from reflecting a given societal reality, constitutes social reality. Neither societal reality nor the ‘natural’ world have fixed, inherent meanings that are being reflected or expressed through language.” (...) “Language is not… expression and naming of the ‘real’ world. There is no meaning beyond language.” (Feminist Practice and Poststructuralist Theory, p. 36,59, translated from the German).

Nancy Fraser, a professor and feminist with an affinity to Queer Theory, isn’t quite as sure about her own philosophy and thus vacillates between a Kantian Dualism and pure idealism. She first defends “a quasi-Weberian dualism” only to assure us later on that “The economic/cultural distinction, not the material/cultural distinction, is the real bone of contention between Butler and me.” (Heterosexism, Misrecognition, and Capitalism, p. 286).

And finally Michel Foucault, the postmodern philosopher and “father of Queer Theory”: "The secret [of sex] does not reside in that basic reality in relation to which all the incitements to speak of sex are situated ... It is [...] a fable that is indispensable to the endlessly proliferating economy of the discourse on sex.” (The History of Sexuality, p. 35.)

To sum up: Queer Theory stands on an idealistic philosophical basis, which says that sex as well as gender are cultural constructs that are continuously “performed”.

As we stated earlier, these intellectual games are not original at all. In Materialism and Empirio-criticism, Lenin shows this by making reference to a number of well-known idealist philosophers. He paraphrases Bishop George Berkeley from the 17th century:

“The world proves to be not my idea but the product of a single supreme spiritual cause that creates both the ‘laws of nature’ and the laws distinguishing ‘more real’ ideas from less real, and so forth.” (Empirio-Criticism, p. 32).

Or let us take Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814):

“Take care, therefore, not to jump out of yourself and to apprehend anything otherwise than you are able to apprehend it, as consciousness and the thing, as the thing and consciousness; or, more precisely, neither the one nor the other, but that which only subsequently becomes resolved into the two, that which is the absolute subjective-objective and objective-subjective.” (Quoted in Empirio-Criticism, p. 68.)

Here, Bogdanov (1873-1928, a Russian revolutionary who was swayed by idealist ideas) states:

“The objective character of the physical world consists in the fact that it exists not for me personally, but for everybody and has a definite meaning for everybody, the same, I am convinced, as for me… In general, the physical world is socially-co-ordinated, socially-harmonised, in a word, socially-organised experience.” (Quoted in Empirio-Criticism, p. 124.)

Lenin commented drily: “[T]his is all one and the same proposition, the same old trash with a slightly refurbished, or repainted, signboard.” (Empirio-Criticism, p. 69.)

And he also points out what the consequences of this philosophical view are. Because if thoughts and reality are actually the same and only constructed by humans, we cannot distinguish between correct ideas (which increase our understanding of the real world) and wrong ideas (which describe the world in a distorted and incorrect way) – it is impossible to tell what helps us to comprehend and change the world, and what is fantasy, utter nonsense: Religion is just as true as physics, the flying spaghetti monster as real as gravity.

“If truth is only an organising form of human experience, then the teachings, say, of Catholicism are also true. For there is not the slightest doubt that Catholicism is an ‘organising form of human experience’.” (Empirio-Criticism, p. 124.)

As a further consequence this also means that we cannot question the subjective reality of anyone, that everybody is right for him or herself (in the realm of “discursive reality”). Who can prove that women aren’t inferior to men? Why shouldn’t it be true that poverty is the result of laziness and personal failure? Why, during a workers’ struggle, isn’t a scab right in their own way? The fact that subjective idealism treats any opinion as valid as any other shows what reactionary role it plays in its practical conclusion.

The claim of Queer Theory and subjective idealism that the whole world is a cultural construct contradicts our daily experience, which is that sexes are real – as sexual reproduction proves on a daily basis – and further that the physical world follows its daily business quite independently of our language. Nevertheless, for some, Queer Theory is seen as a useful tool with which to perceive the world.

Class society, oppression and culture

Queer Theory draws attention to one aspect of gender that cannot be explained by a rigid biological definition: in our society, we are forced into and socialised with gender roles. There is no biological explanation for why pink should be female and blue male; why girls should play with dolls while boys play with Lego; and so on. From a very young age, we are told that women are emotional and irrational, that they are worse mathematicians and shouldn’t tamper with politics, and so on. All of this shows that genders fulfill more than just biological functions, and that they are embedded deeply in the culture of our society.

However, culture itself is not an arbitrary, accidental phenomenon – it emerges from the material base of a society, and from the interaction of humans with nature: “In the process of adapting to nature, in the struggle with its hostile forces, human society develops into a complex class organisation. It is the class structure of society which most decisively determines the content and form of human history, i.e., its material relations and their ideological reflections. By saying this, we are also saying that historical culture has a class character.” (Leon Trotsky, Culture and Socialism)

For the most part of our existence, humans didn’t live in class societies. That is because the existence of class societies requires a surplus product, something one class can enrich itself at the expense of another. In those societies where this wasn’t the case (Engels referred to them as “primitive communism”) there was no women’s oppression either. However, there was a certain division of labour between the sexes (due pregnancy and birth), although most likely this division was not absolute and rigid.

This division of labour, however, did not mean that women were deemed lower than men – on the contrary. As those who ensure the reproduction of our species, they were held in high esteem. Only when humans, in their struggle with nature, found ways of creating a surplus product, which in turn led to the emergence of private property, did the division of labour lead to the oppression of women. In the words of Engels, this was the basis for “the world historical defeat of the female sex” – that is, a historical, not a “biological” event. This means that, while women’s oppression in the last instance does have a biological foundation , it is not an iron natural law. Women’s oppression, over thousands of years, sank deep roots within our society, and it can assume many forms that are not strictly derived from the fact that women can bear children, and were in turn adapted to the respective dominant system.

Oppression is rooted in class society and expresses itself differently in concrete historical circumstances. Gender roles, as well as our dealings with sexuality, have changed many times in the course of human history; and they change according to the prevailing conditions. Examples are pederasty in Ancient Greece, as opposed to today’s homosexuality, or the definition of third genders in some cultures such as the Zapotec people’s Muxes. But also women and men have been assigned different attributes over time, we just need to compare female ideals of beauty during the Renaissance with today’s supermodels.

Women’s oppression under capitalism relies on gender roles to keep intact the economic unit of the “family”, with all the tasks allocated within it, as an important pillar of capitalism. Within the family, it is mostly women who are assigned the role of doing housework, child-rearing and caring for the elderly. The image of women as providing emotional support and motherhood is nurtured. In the job market, in general, women are paid less, and if there is an excess of labour, women are the first to be sent back home. While homosexual couples are being recognised in a growing number of countries, this goes hand in hand with their subordination to the role of the family, including all its responsibilities. Gender roles are thus not purely cultural fantasies derived from the world of ideas, but spring from the material base of class society – which builds upon exploitation and oppression – as well as biological factors.

Oppression, which is also part of capitalist class society, penetrates deeply into our lives and includes the degradation of women to sex objects and their submission to domestic violence. There is very real pressure to move within society as heterosexual men or women. Violence and discrimination against gays and transgender people are rampant, despite numerous liberal campaigns for LGBT rights. The struggle of a transgender person who chooses to undergo hormone therapy or a sex change lasts years and in many cases cannot be afforded. Discrimination in housing, in the workplace and even when simply moving in public spaces, continue to exist.

All these aspects of discrimination and oppression clearly create enormous anger and the desire to escape from this nightmare. Understanding the origin of women’s oppression, and what lies behind discrimination against so-called “deviant” sexualities, is crucial if we are to find a way of ending it. In the absence of an understanding of the material roots of women’s oppression, discrimination of sexuality, and gender roles, ideas such as Queer Theory (that place their entire focus on culture, education and public opinion) inevitably gain popularity. Observing the changeability of gender roles over time, it becomes tempting to draw the conclusion that there are no “actual” biological sexes behind these cultural aspects.

Materialism, science and sex

The idea that sexes are constructed is reinforced by the fact that science under capitalism is not free from the interests of the ruling class. Therefore, science also does not take a neutral stance on the sex/gender question. Let us not forget that the World Health Organization classified homosexuality as an illness until as recently as 1992.

The common, natural scientific understanding of sex is distinctly abstract and rigid (in his Anti-Dühring, Engels calls this kind of thinking the “metaphysical mode of thought”). If we define sex solely on the grounds of XX (female) and XY (male) chromosomes, someone can rightly point out that there are people with distinct XX or XY chromosomes but with atypical hormone levels, as is shown in the scandalous treatment of the athlete Caster Semenya, who is fighting an ongoing battle against being forced to take hormone pills due to her “unfair” testosterone advantage. If we define women solely due to their ability to bear children, are then infertile women not real women? If sexes exist in order to ensure sexual reproduction, why does homosexuality exist? And how can we understand transgender women who have male reproductive organs but identify as women? This “grey area”, the shortcomings of a metaphysical, mechanical materialism, is where Queer Theory hooks into the debate.

Marxists recognise sexes, which enable reproduction, but this doesn’t mean that there are only men and women / Image: Flickr, Eric Parker

Marxists recognise sexes, which enable reproduction, but this doesn’t mean that there are only men and women / Image: Flickr, Eric Parker

However, this problem of absolute and rigid definitions of things is not only posed in relation to sexes. The same questions can be asked in relation to every term that we use. Let’s take the term “house”, for example. A house is a building that provides a roof over one’s head, that one can enter and live in. But is a house without a roof no longer a house? How many holes must a roof have before it ceases to be a roof? At what point does a house in the process of decay become a ruin – and at what point does a house become a castle?

Here we can see that metaphysical materialism, with its rigidity and its claim to unchangeability, necessarily leads to contradictions, which Queer Theory latches on to. No-one would normally think of denying the existence of houses – after all, we have whole cities filled with them. But according to the logic of Queer Theory, the answer would be that there are no houses, since there is no perfect definition of houses that covers every single case accurately. Houses are simply cultural constructs, which are “inscribed” onto random objects.

The metaphysical mode of thought that dominates the natural sciences and education system cannot explain the relation between the individual and the universal. The Marxist dialectic, however, sees a necessary connection between the individual (i.e. an infertile man) and the universal (there is such a thing as men). The universal only exists through its concrete expression – there is no “eternal, complete” house in the world of ideas, but only all actual houses in this world. Lenin describes this in the following way:

“[Let’s] begin with what is the simplest, most ordinary, common, etc., with any proposition: the leaves of a tree are green; John is a man; Fido is a dog, etc. Here already we have dialectics (as Hegel’s genius recognised): the individual is the universal (“because naturally one cannot be of the opinion that there can be a house (a house in general) except all the visible houses.” Consequently, the opposites (the individual is opposed to the universal) are identical: the individual exists only in the connection that leads to the universal. The universal exists only in the individual and through the individual. Every individual is (in one way or another) a universal. Every universal is (a fragment, or an aspect, or the essence of) an individual. Every universal only approximately embraces all the individual objects. Every individual enters incompletely into the universal,etc., etc... for when we say: John is a man, Fido is a dog, this is a leaf of a tree, etc., we disregard a number of attributes as contingent; we separate the essence from the appearance, and counter-pose the one to the other.” (Lenin: On the Question of Dialectics, p. 353)

The quest for an unchangeable, absolute definition is hopeless as the world we live in is constantly changing. Our analyses and terms are an approximation to reality, they describe certain aspects of objective reality. A rigid and abstract (or “metaphysical”) materialism on the other hand tries to force our definitions onto the world no matter what, and demands that it comply with them. Queer Theory, however, takes the rigid, unchangeable definitions of mechanical materialism at face value and argues that the material world itself is rigid and unchangeable – and thus throws out the whole material world, including sexes, declaring them invalid.

In critiquing one crude philosophy, Queer Theory goes to the other extreme and adopts its mirror image. No phenomenon coincides directly with the general categories by which we know them. No man or woman fits perfectly with the universal category that we know them by. Nevertheless, men and women exist. Nature expresses itself in patterns that we as humans can learn to recognise. Our ideas of a man or a woman, stripped away from all the accidental and inessential attributes, are crucial for our understanding of any individual man or woman. Queer Theorists, like their postmodern brethren, however, deny the existence of any form of category or patterns in nature. Instead of understanding the dialectical relationship between the individual and the universal, they renounce the universal and raise the individual and accidental to the level of principle.

So instead of exploring the relationship between the material base (biology, but also the social reproduction of humans in an oppressive class society) and culture, it declares that matter doesn’t exist. It thus absolutises one aspect of reality and degenerates into a “theory” that can’t explain where gender roles and oppression come from and how we can overcome them – in short, into subjective idealism. Lenin described this absolutisation of a part-truth vividly:

“Philosophical idealism is only nonsense from the standpoint of crude, simple, metaphysical materialism. From the standpoint of dialectical materialism, on the other hand, philosophical idealism is a one-sided, exaggerated development (inflation, distention) of one of the features, aspects, facets of knowledge into an absolute, divorced from matter, from nature, apotheosised. Idealism is clerical obscurantism. True. But philosophical idealism is... a road to clerical obscurantism through one of the shades of the infinitely complex knowledge (dialectical) of man. Human knowledge is not (or does not follow) a straight line, but a curve, which endlessly approximates a series of circles, a spiral. Any fragment, segment, section of this curve can be transformed (transformed one-sidedly) into an independent, complete, straight line, which then… leads into the quagmire, into clerical obscurantism (where it is anchored by the class interests of the ruling classes). Rectilinearity and one-sidedness, woodenness and petrification, subjectivism and subjective blindness—voilà the epistemological roots of idealism. [Philosophical idealism] is a sterile flower undoubtedly, but a sterile flower that grows on the living tree of living, fertile, genuine, powerful, omnipotent, objective, absolute human knowledge.” (Lenin: On the Question of Dialectics, p. 361.)

By stating that sexes and sexual desire are constructed, Queer Theory gets tangled up in contradictions. Because the next logical question is, why exactly male and female crystallized as those categories through which humans were separated and oppressed. At this point it digresses into psychoanalytic and anthropological speculations according to which variously the “Law” of incest taboo; language; the Oedipus complex and penis envy; and the lingering influence of the exchange of women in historical societies, created genders and “compulsory heterosexuality.”[1] How hetero-and homosexuality can exist in the animal kingdom, which doesn’t know language, and how societies without the incest taboo managed to reproduce are only two of the many riddles in this line of argument. Confronted with reality, Queer Theory is incapable of explaining it and hits a wall. As an answer to the question “why exactly men and women?”, Butler ultimately writes:

“We have already considered the incest taboo and the prior taboo against homosexuality as the generative moments of gender identity, the prohibitions that produce identity along the culturally intelligible grids of an idealized and compulsory heterosexuality. That disciplinary production of gender effects a false stabilization of gender in the interests of the heterosexual construction and regulation of sexuality within the reproductive domain.” (GT, p. 172, our emphasis)

And after all the books and texts that explained to us in opaque language that sexes are fictitious and a cultural construct, in a shameful and well-hidden manner, nature squeezed its way back in: it is sexual reproduction that determines genders.

Marxists recognise that there are sexes, and that these sexes enable the reproduction of humans. Overall, a large majority of humans can be assigned the female or male sex. In dialectics, there is what is called a “qualitative leap”, a point at which gradual, quantitative change turns into new quality. (An example often used is boiling water which, after a “quantitative” build-up of heat, turns into vapour). With humans as well, there are a number of factors that, put together, allow us to clearly state that a person is male or female.

However, this doesn’t mean that there are only men and women. There is also intersexuality. And there are also transgender persons who have a gender identity that does not match their reproductive organs, and non-binary persons who are neither male nor female. It would be preposterous to accuse them of having a “wrong consciousness” because their identity doesn’t match their reproductive organs. A person’s identity is a very complex thing made up of a combination of biological, psychological and social factors – which ultimately can all be explained materially. But the fact that our consciousness, the human brain, is not yet fully explored scientifically to determine to which extent what factors create our gender identity, does not give us any reason to declare them a purely “cultural fiction” that isn’t connected to our body.

On the contrary, this depiction of identity as cultural construct blurs the very real problems of many transgender persons in their struggle to gain access to sex reassignment surgery or hormone therapy. Quite practical demands, such as the right to abortion for women, free hygiene products or gender-specific medicine (gynaecology) cannot be argued for either.

The powerful discourse of power

If we assume, as Queer Theory does, that sexes and sexuality are cultural constructs we have to ask: how did this construct come to be, and why?

Judith Butler makes fun of Friedrich Engels and “socialist feminists” as they try to “locate moments of structures within history of culture that establish gender hierarchy.” Butler herself believes that past societies in which there was no women’s oppression are “self-justificatory fabrications.” (Gender Trouble p. 46.) That it has been proved that such societies actually existed only shows her ignorance towards reality and her rejection of history.

While the Marxist explanation is far too “simplifying” in the eyes of Queer Theory, it presents other explanations for the “construction” of oppression in society, which supposedly stems from the multi-layered, many-faceted and complex power relations and structures in society.

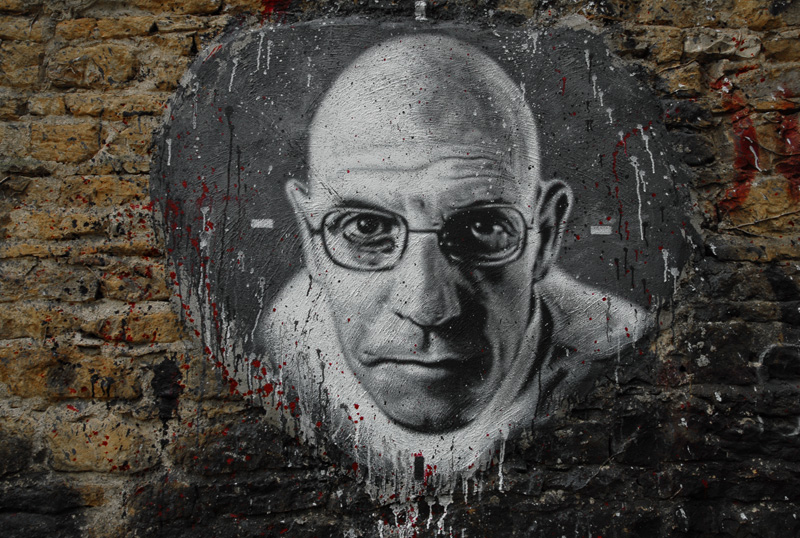

The concept of power that Queer Theory advocates is borrowed from the French philosopher Michel Foucault (1926-1984), who in academic circles is sometimes seen as a successor or “enhancer” of what they call “orthodox Marxism”. As a pupil of Louis Althusser, he moved in the orbit of the French Communist Party (PCF) for a while and was an (inactive) member from 1951-1952, without ever having studied Marxism (as he admits himself).[2]

During the revolutionary events of May ‘68, Foucault was teaching at a university in Tunisia when massive student protests were taking place. He saw his task as teaching “something new” to the students who, in his words, were strongly influenced by Marxism.

The historic betrayal of the general strike and the mass movement in France by the leadership of the PCF and the failure of the revolution, he considers as being the fault of a “hyper-Marxism” in the country at that time. He classifies this period of intense class struggle as a language game, a search for vocabulary:

“Thinking back to that period, I would say that what was about to happen definitely did not have its own proper theory, its own vocabulary... I mean, reflecting on Stalinism, the politics of the USSR, or the oscillation of the PCF in critical terms, while avoiding the language of the right, was a complex operation that created difficulties." (Remarks on Marx, p. 110-111.)

Despite his counterproductive role in the real movement and despite the fact that Foucault developed his views consciously against Marxism, there is this idea among university circles that he had an affinity with Marxism and that his ideas are progressive and a good connecting point for resistance.

For Queer Theory, his most influential work was The History of Sexuality (1976), in which he tries to trace the history of the discourse of sexuality in modern history and in which his understanding of power plays a central role. According to Foucault (and Queer Theory), power permeates all spheres of life and expresses itself in pairs of opposites: old-young, man-woman, homo-hetero, etc. This is often described as the Western obsession with binarity (pairs of opposites), which was “invented” by Western philosophy.

The notion of "power", as advanced by Michel Foucault, is a central tenet of Queer Theory / Image: Flickr, Thierry Ehrmann

The notion of "power", as advanced by Michel Foucault, is a central tenet of Queer Theory / Image: Flickr, Thierry Ehrmann

“Power”, according to this concept, has an interest in maintaining an unfair judiciary, the medical-scientific discourse of man and woman, religion, as well as repressive educational systems. It forms class interests of the rulers, the male will to patriarchal oppression, as well as state repression. It also created norms and prohibitions pertaining to sexual practices.

“[J]uridical power must be reconceived as a construction produced by a generative power which, in turn, conceals the mechanism of its own productivity,'' says Butler. (GT, p. 121.) So: power produces power and then hides the fact that it was produced by power.

But power is even more powerful: it not only produces oppression but also resistance. Oppression and resistance are just another binary pair of opposites, just like “old-young” or “man-woman”, constructed by discourse. Power produces the discourse of rebellion, the fiction that something can be done against oppressors, the illusion that there could be a world without power. From this logic, Foucault goes as far as to “analyse” the demise of absolute monarchies through bourgeois revolutions as a result of a power discourse on justice:

"These great forms of power functioned as a principle of right [...] such was the language of power, the representation it gave of itself... In Western societies since the Middle Ages, the exercise of power has always been formulated in terms of law. A tradition dating back to the eighteenth or nineteenth century has accustomed us to place absolute monarchic power on the side of the unlawful." (The History of Sexuality, p. 87.)

How ridiculous and simplifying is the materialist, Marxist analysis that the emergence of a capitalist mode of production overturned the old feudal order! No, it was “tradition” that led us to suddenly believe that monarchy was unjust and overthrow it! This is the result of a theory that views history as a construction of discourses.

Within this self-referential power cycle, however, none of the Queer texts provides us with a coherent explanation of what power actually is. In the very first sentence of his lectures on power, Foucault states: “The analysis of power mechanisms is not a general theory of what constitutes power.” (Vorlesung zur Analyse der Macht-Mechanismen, p. 1, own translation)

To give the reader a feeling of how Foucault tries to grasp Power we will pass the word to the author himself and apologise for the lengthy quote:

“It seems to me that power must be understood in the first instance as the multiplicity of force relations immanent in the sphere in which they operate and which constitute their own organization; as the process which, through ceaseless struggles and confrontations, transforms, strengthens, or reverses them; as the support which these force relations find in one another, thus forming a chain or a system, or on the contrary, the disjunctions and contradictions which isolate them from one another; and lastly, as the strategies in which they take effect, whose general design or institutional crystallization is embodied in the state apparatus, in the formulation of the law, in the various social hegemonies. Power's condition of possibility... must not be sought in the primary existence of a central point, in a unique source of sovereignty... it is the moving substrate of force relations which, by virtue of their inequality, constantly engender states of power, but the latter are always local and unstable. The omnipresence of power: ... because it is produced from one moment to the next, at every point, or rather in every relation from one point to another. Power is everywhere; not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere. ...Power is not an institution, and not a structure; neither is it a certain strength we are endowed with; it is the name that one attributes to a complex strategical situation in a particular society." (The History of Sexuality, p. 92-93.)

Amen!

It is not surprising that Foucault wrote The History of Sexuality under the effects of an LSD trip. Engels once wrote that scientists, whenever they fail to understand a phenomenon, tend to invent a new “force” to serve as an explanation:

“[I]n order to save having to give the real cause of a change brought about by a function of our organism, we fabricate a fictitious cause, a so-called force corresponding to the change. Then we carry this convenient method over to the external world also, and so invent as many forces as there are diverse phenomena.” (Dialectics of Nature, ch. 3.)

This is a very apt description of what “power” and “force relations” are for Foucault and Queer Theory. Power is the all-embracing, quasi-God-like entity that describes everything, that in one moment creates discourses and in the next is itself a product of discourse. It is the all-pervading spirit that no-one eludes that binds us forever – after all, we are also creations of power! The absurdity of this power fantasy shows how idealism, no matter how modern it appears, in the last instance always leads to religious obscurantism, as Lenin said. And lastly: something that is everything, a Being free of contradictions and resistance that has always been, in the end is just… nothing.

Queer Theory goes further into the question of "binary" opposites, which it sees as a fundamental problem to be dealt with. But binaries (or opposites as Marxists would call them) are intrinsic parts of nature. The Greek philosopher Heraclitus once wrote that "there is harmony in strife, like the bow and lyre". Hot and cold, attraction and repulsion; north and south, positive and negative currents, as well as male and female, are all examples of the interpenetration and unity of opposites, which is the basis of all change in nature, and change is the mode of existence of nature. Wishing away male and female sex is like wishing away the south pole, or cold air. Ironically, Queer theorists themselves seem to forget that wishing away binaries is in itself a “binary opposite” of the existing binary state of things.

Resistance is futile!

If we remain in the natural habitat of Queer Theory, the world of academic papers, this debate seems like an intellectual thrill in which one passes philosophical quotes back and forth. However, as we wrote at the beginning, philosophical premises also lead to certain practical conclusions.

The omnipresence of power in Queer Theory means that we can never escape from it, that every resistance is only an expression of power itself and ultimately serves stability. Hence, Foucault’s relatively well-known quote that resistance “is never in a position of exteriority in relation to power”, and that therefore there are only “possible, necessary, improbable, spontaneous, savage, solitary, concerted, rampant or violent… quick to compromise, interested or sacrificial” resistances. (History of Sexuality: 95-6.)

“Recent insights and practices surrounding “queer”, question the belief in the possibility of long-term social change or emancipation in general.” (Jagose, p. 61.)

This absolute pessimism toward social movements, the belief that any resistance is automatically doomed, shows how little these philosophers understood of the revolutionary movements of the 1960s and 1970s and the reasons for their failure. They reflect the hopelessness of the feminist deadlock, of the petty bourgeoisie that doesn’t trust the working class (if they even believe it exists). Instead of understanding and criticising the role of the mass organisations’ leadership, they look for new ways of “resistance” without a clear idea against who or what this resistance should be directed, and what methods should be used. The possibility of an overthrow of the ruling system appears unfeasible and impossible.

As a consequence, Queer Theory suggests a practice that makes even the mildest reformism look radical. It retreats completely into the field of culture and language. There should be new “terms” for identity, a “new grammar” developed or a “new ethic” drawn up (Gayle Rubins). For instance, in order to “expose” the illusion of sexes, Butler suggests parodying gender identities through “cultural practices of drag, cross-dressing and the sexual stylization of butch/femme identities.” (GT, p. 137.) This is the only practical suggestion in the whole book Gender Trouble! And Nancy Fraser, relieved, explains:

“The good news is that we do not need to overthrow capitalism in order to remedy [the economic disadvantage of gays] – although we may well need to overthrow it for other reasons. The bad news is that we need to transform the existing status order and restructure the relations of recognition.” (p. 285.)

Read: we need to improve the image of homosexuality. Here, Fraser, who is comparatively more practically inclined, openly displays her reformism: luckily she doesn’t have to overthrow capitalism! She only has to change how society views homosexuality! It is no wonder that Queer Theory has been willingly taken up by some reformists within the workers’ organisations in order to evade the responsibility of leading an actual struggle against discrimination with strikes, mass protests, in short, methods of class struggle, and instead focus on demands for language reforms, quotas, cultural free spaces and rainbow-coloured crosswalks.

By omitting the class question, Queer Theory is not only a useful tool in the hands of bureaucrats within the workers’ organisations, it also serves as an ideological justification for a section of the bourgeoisie and capitalist forces to present themselves as LGBT-friendly and paint a liberal and progressive image of themselves. Corporations such as Apple or Coca Cola, who exploit tens of thousands of people in terrible working conditions, support LGBT campaigns in their companies or finance party-trucks handing out free alcohol at commercialised Pride parades. In order to finance the production of seemingly radical, but actually (for the ruling class) completely harmless ideas, thousands of Euros are spent on gender studies professorships, departments and queer study scholarships, while the left-liberal media and publishers print benevolent articles and novels.

Many queer activists are aware of these tendencies and are clearly against the co-opting of their resistance by the ruling system. However, Queer Theory does not offer the ideas necessary to fight this usurpation by the ruling class; on the contrary it is part of the ruling ideology that individualises and camouflages exploitation and oppression, while dividing the united struggle against the system, precisely because united struggle is alien to Queer Theory.

Despite its origin as a criticism of traditional identity politics of the 1970s and 1980s, with its circle mentality and internal fights, it has failed to overcome precisely this type of identity politics. Since we can’t escape the omnipresence of power in society, it is also impossible to escape identities even though they are seen as fictitious.

Since identifications “are, within the power field of sexuality, inevitable” (GT, p. 40), and we can at best hope to “parody” these identities, Queer Theory, which started out as a critique of identity politics, ends up exactly where it started: with identity politics. In practice, the old squabbles of who may represent whom continue unabashedly, just like in the radical feminist circles (and against them). Butler states aptly: "Obviously, the political task is not to refuse representational politics—as if we could.” (GT, p. 8.)

Any form of collective action and united struggle of all the oppressed becomes a fight, since “unity” and “representation” automatically lead to exclusion and violent oppression: “unity is only purchased through violent excision.” (Butler, Merely Cultural, p. 44.)

This leads to an individualisation of those who oppose the oppressive system under which we live. For instance, queer-feminist Franziska Haug complains that “the identity of the individual – origin, culture, gender etc. – becomes the crux of the matter” in queer-feminist debates, and “the right to speak and fight is being decided depending on the identity of the speaker” (Haug, p. 236.). There is a competition about who is the most oppressed and thus has the right to speak, and who can’t be opposed. Against unwelcome arguments we often hear accusations along the lines of “you, being a white man / cis-woman / white trans-person don’t have the right to disagree with me, or revoke my subjective point of view.”

While trying to exclude no-one through “violent generalisations”, a countless number of identities are created that are supposed to cover all thinkable combinations of sexual, romantic, gender and other preferences and that are being administered in a range of queer-cliques. Instead of a united struggle of all who want to fight against the system, this logic often leads to mobbing and exclusion within different groups. One queer-feminist gives a vivid account of this in her paper, “Feminist Solidarity after Queer Theory” which almost reads like a desperate and intimate diary entry:

“Despite my qualms about the term bisexual, this descriptor provides a kind of home for me, when everywhere else feels worse. Both heterosexual and lesbian spaces have their own comforts for women, and I have often been excluded from both. I have also been told that I needed to change to fit into those spaces—by acceding either to my true hetero-or-homosexuality—and I have felt the moments of truth as well as the sometime hypocrisy and complacency of those demands… It is both necessary and troubling to seek out a home as a gendered or sexual being: necessary because community, recognition, and stability are essential to human flourishing and political resistance, and troubling because those very practices too often congeal into political ideologies and group formations that are exclusive or hegemonic.” (Cressida J. Heyes, 1,097)

From these lines we can sense the misery created by the pressures and the oppression of capitalism and what they do to our psyche and self-esteem. But it also shows the deadlock of identity politics. Even though the text sets itself the task of finding a form of solidarity between all feminists, it can’t imagine a unity that isn’t based on identity. In practice, identity politics leads to a split in the movement. For instance, in Vienna there have been two separate marches on women’s day on 8 March for years: one by the radical feminists (which can only be attended by women and, in one block, by LGBT persons), and one by the queer-activists (where at first no cis-men, but since 2019, all who see themselves as feminists can attend). A united demonstration was repeatedly declined by both sides. Against the background of the upswing of mass movements surrounding demands for women’s rights around the globe, and the dormant potential in Austria under a right-wing government, this example reveals the divisive role of identity politics.

It is only natural that many people, in particular young people, question established norms in society such as sexuality and gender roles. This has always been the case and as Marxists we defend the rights of all people to express themselves and identify however they want to. But the problem arises here when the personal experience of individuals is theorised, raised to the level of a philosophical principle and generalised for the whole of society and nature. The Queer theorists tell us that being queer or non-binary is progressive and even revolutionary, as opposed to being binary (i.e. man or woman, which the vast majority of humanity is), which is deemed reactionary. Here, however, it is Queer Theory that shows its reactionary side. For all its radical talk against oppression, it opposes a united class struggle and promotes atomisation of individuals on the basis of sexual and personal preferences, dividing the working class into ever smaller entities. Meanwhile, the whole rotten exploitative and oppressive edifice of capitalism remains in place.

For working-class unity!

For Marxists, unity in struggle is based neither on culture or identity, and nor is it a moral question. Instead, we emphasise the necessity of the unity of the working class as the only force that can end exploitation and oppression, due to its role in the productive process of capitalism.

Our society is fundamentally defined by how we produce, because the production of food, houses, energy – everything that we need to live – is the basis for how we can lead our life. Is there enough food to allow for the development of science and culture beyond mere survival? Can science develop our means of production so that the amount of work can be reduced and time can be freed up for research, education and so on? The economic base determines how we work and live in our society and, as a consequence, which morals, laws or values are dominant (although this relation is not mechanical, as Marx’s critics like to claim, but dialectical.)

Marxists emphasise the necessity of the unity of the working class as the only force that can end exploitation and oppression / Image: fair use

Marxists emphasise the necessity of the unity of the working class as the only force that can end exploitation and oppression / Image: fair use

Our society is divided into classes that are not defined culturally by whether someone is rich or poor (rather this is a consequence of the class someone belongs to). Classes are determined by the role they play in the process of production. In capitalism, the main classes are the capitalists, who own the means of production such as factories and land, and the working class, which has to sell its labour power in order to survive from the wages earned. The contradiction lies in the fact that the large majority of people produce socially in factories and companies in a world-wide division of labour, while the fruits of their labour are appropriated privately by a tiny minority. As this minority of capitalists produces in competition with each other, under the anarchy of the world market and only for their own profits, this leads to periodic crises, and is the reason why our society’s resources cannot be used to guarantee a decent living for all of humanity. This exploitation is the decisive basis for oppression and discrimination. Socialism means solving the contradiction of social production/private ownership by taking production into our own hands, under the control of society, that is, by expropriating the parasitic minority of capitalists.

From this, it follows that the unity of the working class is rooted in the present conditions. A good life for the working class – higher wages, shorter working hours, a high-quality welfare system – can only be realized against the interest of the capitalists, because this would directly cut into their profits. Marxists see it as their task to make this shared interest of the working class as visible as possible to strengthen our unity, because only together can we overthrow this exploitative system. That is why Marxists fight decisively against any kind of division; that is, against racism, sexist prejudices and other forms of discrimination, regardless of whether the proponent of such views is a politician, a capitalist or a fellow worker. We are against any form of discrimination, but in contrast to identity politics we don’t perceive the interests of different genders, sexual orientations, etc., as fundamentally opposed to each other. On the other hand, the different class interests are (i.e. one must lose if the other wins).

Objectively, there is enough wealth in our society to make a comfortable life possible for everyone. There is enough food, and we have the technology to reduce the working hours drastically and still get all the tasks of society done. We also fulfill all prerequisites for the socialisation of domestic work (cleaning, cooking, child rearing, elderly care…), which today is to a large part done within the institution of the family. This could be achieved by opening communal kitchens and public kindergartens, and investing in a good welfare and healthcare system. These measures would eliminate the material basis of the capitalist family, which locks women into an oppressive cage and is the basis for gender-and-sexuality-based discrimination. Without material pressure and dependency, human relations could evolve into truly free associations, which would be a step forward for all women and men. Science, education, culture and language would be freed from the profit motive and the interests of the ruling class, which are constantly dividing us and keeping us down. Human culture could reach unimaginable heights. In comparison, the modest demands of queer-theoreticians for new vocabulary and free spaces show how limited they are within the narrow confines of capitalism.

This, of course, does not mean that cultural achievements will happen “automatically” or “by themselves” simply by expropriating the big corporations and banks. But we must grasp the real relationship between material base and culture, between revolution and language concretely.

The act of revolution means the entering of the masses onto the stage of history. It is the process of the masses taking their destiny into their own hands and no longer letting their lives be dictated by others. In all historical revolutions, the working masses have unleashed incredible creativity and set about removing the rubbish of the old society.

In his text “The Struggle for Cultured Speech”, Trotsky describes how, after the Russian Revolution, the struggle against abusive language and swearing was carried out. In an extremely backward country that had only just begun to take up the task of revolutionising society, at a time when “philosophy of language” wasn’t even yet a term, workers from a shoe factory called the “Paris Commune” decided in a general assembly to stamp out bad language in their workplace and to impose punishment if this decision was breached. Trotsky writes:

“Revolution is, before and above all, the awakening of humanity, its onward march, and is marked with a growing respect for the personal dignity of every individual with an ever-increasing concern for those who are weak… And how could one create day by day, if only by little bits, a new life based on mutual consideration, on self respect, on the real equality of women, looked upon as fellow-workers, on the efficient care of the children—in an atmosphere poisoned with the roaring, rolling, ringing, and resounding swearing of masters and slaves, that swearing which spares no one and stops at nothing? The struggle against ‘bad language’ is a condition of intellectual culture, just as the fight against filth and vermin is a condition of physical culture.”

This struggle is not linear, nor is it easy, because consciousness develops in a contradictory manner. As Trotsky pointed out in the same text:

“A man is a sound communist devoted to the cause, but women are for him just ‘females,’ not to be taken seriously in any way. Or it happens that an otherwise reliable communist, when discussing nationalistic matters, starts talking hopelessly reactionary stuff. To account for that we must remember that different parts of the human consciousness do not change and develop simultaneously and on parallel lines. There is a certain economy in the process. Human psychology is very conservative by nature, and the change due to the demands and the push of life affects in the first place those parts of the mind which are directly concerned in the case.”

The struggle for a comradely, humane culture is therefore not simply over and done with after a revolution. However, the revolution creates the conditions in which the united, common struggle for such a culture can be developed freely and truly self-determined. This was actively supported after the Russian Revolution, when women revolutionaries were sent out into the whole country and promoted massive educational programmes and organisational efforts. This Zhenotdel movement was later shut down by Stalin in 1930. Trotsky said, about the role of women revolutionaries, that they have to be the moral battering ram in the hands of a socialist society that breaks through conservatism and old prejudices.

“But there again the problem is extremely complicated and could not be solved by school teaching and books alone: the roots of contradictions and psychological inconsistencies lie in the disorganization and muddle of the conditions in which people live. Psychology, after all, is determined by life. But the dependency is not purely mechanical and automatic: it is active and reciprocal. The problem in consequence must be approached in many different ways—that of the ‘Paris Commune’ factory men is one of them. Let us wish them all possible success.” (Ibid)

A huge gulf lies between the management-sanctioned, tokenist LGBT-campaigns of today, where class exploitation and psychological alienation from ourselves are still upheld, and the campaign organised by the workers of the “Paris Commune” shoe factory, who had full control over their own working conditions – including the language culture! It isn’t hard to imagine which of these two would take deeper roots and work more thoroughly.

The aim of achieving a humane culture and language is understandable and correct, but the political orientation of creating a new language of equality, without also tackling the real social inequality is a dangerous illusion and, in the end, an impasse. A truly humane and free culture will be born out of the common struggle for emancipation of the working class, which will mold our consciousness, breaking through generations of prejudice and will throw present-day monstrous discrimination, racism, sexism, violence and degradation of women and minorities to the dustbin of history.

Last but not least: should we call ourselves Queer-Marxists?

What we have explained above has shown that, beginning with an understanding of what the world actually is, of how (or if) we can change it and with the practical conclusions that flow from this, Queer Theory and Marxism are irreconcilable theories. And yet, time after time, attempts are made to combine them and portray them as being mutually compatible.

Rarely are these efforts more than a clumsy effort to appropriate the label of Marxism to give oneself a degree of radical credibility, while completely distorting its essence in the process. There are, however, some on the left, with honest intentions no doubt, who argue that we should adopt the label “Queer Marxism”.

The most common argument raised by these people is that there is “something missing” from Marxism, i.e. that is unable to comprehend the specific oppression of sexualities. It should be obvious from the present article that we have provided sufficient arguments to counter these claims.

Attempts to reconcile Queer Theory and Marxism inevitably result in distortions / Image: FULBERT

Attempts to reconcile Queer Theory and Marxism inevitably result in distortions / Image: FULBERT

However, another popular argument has to do with tactics, which goes more or less like this: one should stand on a firm, Marxist base, but in order to make Marxism more appealing to people of all identities, and because of its bad reputation, calling oneself Queer Marxist can send a clear signal of inclusiveness. And what harm could it do if it doesn’t work immediately? If it doesn’t help it doesn’t hurt, goes the argument.

A relatively extensive demonstration of this way of thinking is provided by Holly Lewis in her book The politics of everybody (2016) which we will therefore deal with briefly here.

In her book, Lewis refers rather self-consciously to the “old, unfashionable approach of Marx’s materialism”, including its orientation towards the working class in order to change the world. (Lewis, p. 91.) She wrote her book purportedly to render Marxism tempting for queer and feminist activists and conversely to acquaint Marxists with the politics and origins of feminist, queer and trans politics. (Lewis, p. 14)

On the surface, Queer Marxism might appear to some as a good way of winning queer people to Marxism and integrating them into the struggle against capitalism. But stating that we need a “Queer Marxism" inevitably leads down the road of differentiating it from “Classical Marxism”, precisely to justify why there has to be a “Queer Marxism” in the first place. This creates a fissure between the two and opens the door through which alien class ideas and ideological concessions seep in.

After spending a good third of her book trying to explain the fundamentals of Marxism, Holly Lewis arrives at exactly this point. As a feminist Queer Marxist she wants to incorporate international queer, trans and intersex perspectives into the materialist, Marxist analysis of sex and gender. (p.107)

And what are these particular perspectives that in her view can explain the specific forms of oppression better than “boringly normal” Marxism? Here, all the old arguments are unpacked, such as Marx and Engels being children of their time and therefore, of course, sexist, with Engels being a bit more of a sexist than Marx. Then she constructs, as revisionists often do, an alleged contradiction between Marx and Engels, with the latter supposedly not correctly grasping the nature of women’s oppression, which his book The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State apparently confirms. She rejects the Marxist understanding of the role of the family in capitalism and gradually undermines the very foundations of Marxism, including its historical-materialist analysis. In regard to the gender question, she finally gets to the point of vague and unclear formulations about the alleged (in-)existence of genders.

However, even on this blurred philosophical basis it is almost impossible for her to employ any aspect of Queer Theory in a positive way. But she does find a straw to clutch at: the concept of performance, which postulates that gender roles are internalised through repetitive actions.

“Far from being incompatible with materialist analysis, Butler’s intervention meshes nicely with Fields’[3] conception of ideology as a repetition of actions originating in social relations, but actions that continue to be normalized through habit, experience, and the organizational logic of a given society.” (Lewis, p. 199.)