One Step Forward, Two Steps Back (The Crisis in Our Party) sees Lenin analysing the fallout of the Second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). The 1903 Congress saw the famous split emerge in the Russian workers’ movement between Bolshevism and Menshevism. However, the split didn’t initially concern differences in politics and perspectives, erupting over seemingly secondary organisational questions. Only in subsequent years, particularly around the 1905 Revolution, would those differences become sharply apparent, culminating in a formal and final split between the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks in 1912.

During and immediately after the Congress, Lenin was castigated for ‘dictatorial’ conduct by his adversaries, allegations reinforced by the slanders of bourgeois historians. But his account paints a very different picture. In this pamphlet, he draws out the real political content of disagreements over seemingly trivial, organisational matters, which were to later acquire decisive importance.

[To read more about this important period in Lenin's life and in the history of Russian Marxism, we highly recommend chapters 7 and 8 of Rob Sewell and Alan Woods' new biography, In Defence of Lenin, available from Wellred Books.]

‘In Defence of Lenin’ is now available to pre-order!

— Wellred Books (@WellredBooks) November 23, 2023

Over two volumes, Rob Sewell and Alan Woods trace Lenin’s life and explain his ideas, drawing on the tremendous heritage of what he actually wrote and did.

Pre-order now: https://t.co/POcbzWgf1R 🚩 pic.twitter.com/EoBeod5HaK

From small circles to a professional party

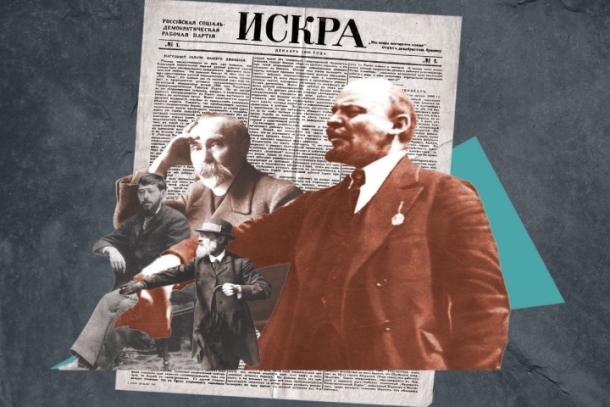

Lenin had long been struggling against the amateurism of the embryonic forces of Russian Marxism / Image: The Communist

Lenin had long been struggling against the amateurism of the embryonic forces of Russian Marxism / Image: The Communist

Lenin had long been struggling against the amateurism of the embryonic forces of Russian Marxism, particularly as new strike waves signalled a revival of the class struggle in the country.

The RSDLP had been subject to severe repression, with leaders arrested and exiled following its 1898 founding congress in Minsk. In these conditions, discipline and cohesion were essential.

From exile in Western Europe, Lenin struggled against the prevailing methods of informality and what he called a ‘small-circle mentality’. In their place, he advocated for a party of professional revolutionaries – ideologically trained in Marxist theory, which Lenin always emphasised – under a common centre and discipline.

This struggle was conducted using the newspaper Iskra (‘the Spark’), which was produced abroad and smuggled into Russia. Despite having just nine agents in Russia at the end of 1901, Iskra struck a chord with an advanced layer of Russian workers and rapidly gained support.

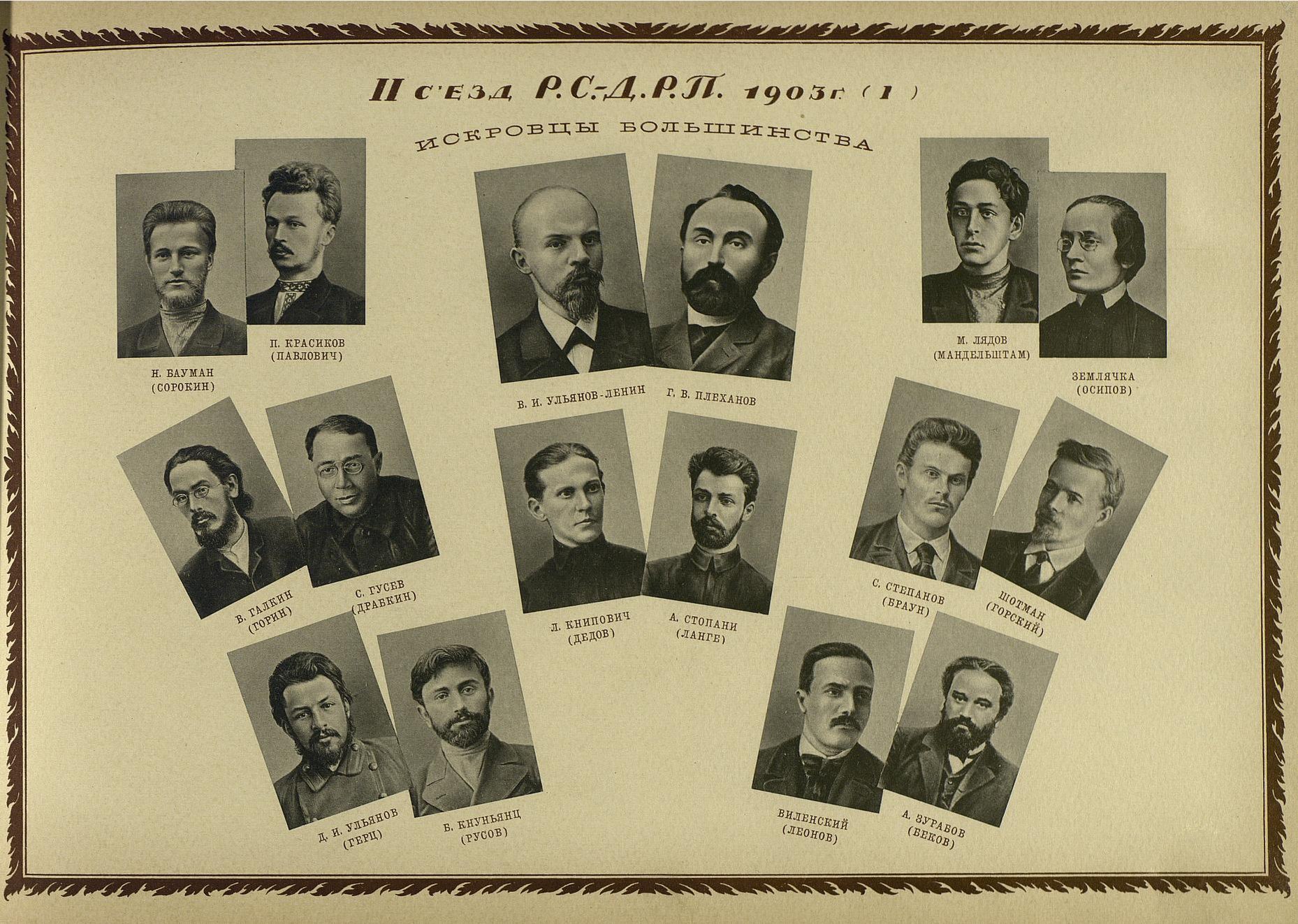

The six-member emigre editorial board (Lenin, Plekhanov, Axelrod, Zasulich, Martov and Potresov) moved to London in 1902. Its authority grew with Iskra’s readership and expanding network of agents. But while the Iskra tendency was developing into the dominant trend in Russian Marxism, tensions were building within its leadership.

Despite his exemplary role as the ‘grandfather of Russian Marxism’, Plekhanov began to feel events overtaking him, and the wounding of his prestige made him especially difficult to work with. Meanwhile, the other ‘veterans’ of his Emancipation of Labour Group had made no real contributions for years yet still occupied key positions. Some of these veterans also expressed their discomfort at Lenin’s scathing criticism of the liberals, foreshadowing future political disagreements.

Nevertheless, the Iskra editorial board was united in its opposition to the likes of the Jewish Bund, which opposed the formation of a centralised party in favour of loose federalism; and against the so-called Economists (organised around the Rabocheye Dyelo newspaper), which attempted to blunt the political edge of Russian Marxism by focussing exclusively on economic ‘bread and butter’ questions.

The calling of an official second congress of the RSDLP by Iskra for 1903 was expected to confirm the fact that the Iskraists had won the battle against revisionist trends. In fact, to the surprise of all its participants, the Congress brought to the fore deep disagreements among the supporters of Iskra themselves.

A house divided

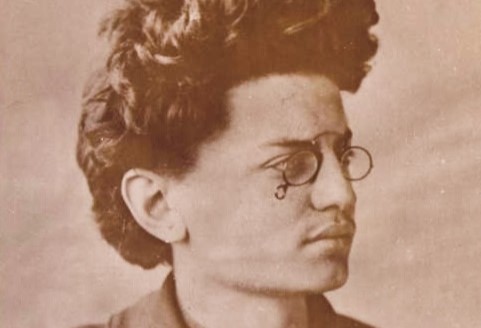

The Congress finally convened on 17 July 1903 in Brussels, though police scrutiny forced its relocation to an angler’s lodge in London. 43 delegates were in attendance, including a 23-year-old Leon Trotsky. Lenin recognised the ‘young eagle’ as a talented polemicist and writer, and hoped he would be his ‘cudgel’ in the debates. A few delegates were deported before the close of business, partly because a member of the organising committee was an Okhrana agent.

The Iskra group started with a firm majority of 33 votes. However, as proceedings wore on, divisions opened within the faction, first during the 22nd session, over the Party rules. Lenin’s draft on membership criteria read: “A member of the RSDLP accepts its programme and supports the Party both financially and by personal participation in one of the party organisations.” Meanwhile, Martov simply called for “regular personal cooperation under the direction of one of the party organisations.”

This subtle distinction reflected Martov’s conciliatory attitude towards petty-bourgeois and intellectual ‘fellow travellers’ in the Party’s orbit. Axlerod expressed this clearly when he stated:

“[L]et us take for example a professor who regards himself as a Social Democrat and declares himself as such. If we adopt Lenin’s formula we shall be throwing overboard a section of those who, even if they cannot be directly admitted to an organisation are nevertheless members…”

These were exactly the types who needed throwing overboard! In muddying the water between members and academic sympathisers, Martov’s proposal showed the lingering influence of a ‘small-circle mentality’, characterised by loose organisation and a predominance of personal relations over politics. Lenin replied:

“Martov’s formulation… serves the interests of the bourgeois intellectuals, who get shy of proletarian discipline and organisation… To people accustomed to the loose dressing-gown and slippers of the Oblomov circle domesticity, formal Rules seem narrow, restrictive, irksome, mean, and bureaucratic, a bond of serfdom and a fetter on the free ‘process’ of the ideological struggle. Aristocratic anarchism cannot understand that formal Rules are needed precisely in order to replace the narrow circle ties by the broad Party tie.”

Nevertheless, Lenin offered to concede ground over this matter, saying it need not lead to a split in the Party.

A bloc between the right (delegates from Rabocheye Dyelo and the Jewish Bund) and a wavering Iskraist ‘marsh’ saw a vote of 28 to 23 for Martov. But this result was reversed after the 27th session, in which delegates from the Jewish Bund demanded a monopoly on all matters pertaining to Jewish workers in Russia. This unacceptable federalist conception, based on nationalist prejudices, was overwhelmingly defeated (41-5) with Lenin, Plekhanov, Martov, and Trotsky voting against, and the latter passionately speaking in opposition. This provoked a walkout by the Bundists.

🚨Only 100 days to go until the World School of Communism 🚨A week of the highest quality political discussions on a wide array of topics, including the founding of a Revolutionary Communist International!

— In Defence of Marxism (@marxistcom) March 1, 2024

Communists of the world, head to the link in our bio and sign up! pic.twitter.com/u6iXpjOEmv

They were soon followed by supporters of Rabocheye Dyelo, after the Congress recognised Lenin and Plekhanov’s rival League of Revolutionary Social Democrats as the sole representatives of the party abroad. The changed composition meant Lenin was left with a majority (the Russian word for which, bolshinstvo, inspired the name of his Bolshevik faction), with Martov in a minority (menshinstvo, or Menshevik).

But divisions within the Iskraists came out sharply once more over the composition of the paper’s editorial board and the Party’s central committee. Lenin called for a leaner editorial board of three, and the removal of those ‘veterans’ who no longer contributed seriously to the political work from both bodies.

All he wanted was a functioning leadership for the Party and its organ, which a three-person editorial board would facilitate by ensuring a clear majority on all decisions. Still, the proposal provoked an almighty row, with Trotsky (who later admitted that he was still infected by a certain youthful sentimentality for the old veterans) denouncing Lenin as a dictator.

Lenin was taken aback at the reaction, especially as he had presented this proposal to the old editorial board without controversy. He correctly identified the real crux of the matter as, once again, stemming from old habits, where considerations about individuals’ wounded pride were given precedent over the interests of the Party:

“Such arguments simply put the whole question on the plane of pity and injured feelings, and were a direct admission of bankruptcy as regards real arguments of principle, real political arguments.”

Thanks to the absence of the Bundists and Economists, Lenin was able to win a majority, but despite being invited onto the editorial board as a representative of the minority faction, Martov petulantly refused to take up the position.

Drawing the lessons

While formally victorious, Lenin was distressed at the results of the Congress / Image: public domain

While formally victorious, Lenin was distressed at the results of the Congress / Image: public domain

While formally victorious, Lenin was distressed at the results of the Congress, which saw the delegates depart amidst acrimony and rumblings of a split.

The Martov faction wasted no time in denouncing Lenin’s “dictatorial tendencies” and “ruthless centralism”, despite the latter’s multiple attempts at collaboration. Trotsky wrote scathing appraisals of Lenin’s ‘Jacobinism’ in the aftermath, which Lenin accepted with some pride, replying, “A Jacobin who wholly identifies himself with the organisation of the proletariat is a revolutionary Social-Democrat”.

Trotsky would soon after break with the Mensheviks, and later repudiate his youthful errors, writing in his autobiography, years after Lenin’s death: “The break with the older ones who remained in the preparatory stages, was inevitable in any case. Lenin understood this before anyone else did.”

Contrary to the allegations against Lenin, it was the Menshevik faction who acted in a disgracefully anti-democratic manner. They launched a wrecking campaign, founding a shadow Central Committee in anticipation of a potential split, and slandered Lenin in the foreign press, which they controlled.

Martov scandalously accused Lenin of fomenting a ‘state of siege’ in the Party, simply for attempting to carry out the democratic mandate of its sovereign Congress, which Martov himself refused to respect.

In the end, Plekhanov, who had initially sided with the Bolsheviks, wavered and switched sides, allowing the Mensheviks to recapture control of Iskra in September 1903, despite having only minority support at the Congress. All of this exacted a toll on Lenin. After recovering from the ordeal, he set about writing One Step Forward, Two Steps Back, and set the record straight.

He drew the necessary conclusions about the fundamental source of the disagreements at the Second Congress. A rupture had opened up between the ‘hard’ revolutionary wing of the party, and opportunists who had a ‘soft’ attitude to the liberals and petty-bourgeois fellow travellers, and were unwilling to build the fighting proletarian party necessary to secure victory:

“The minority was formed of those elements in the Party who are least stable in theory, least steadfast in matters of principle. It was from the Right wing of the Party that the minority was formed. The division into majority and minority is a direct and inevitable continuation of that division of the Social-Democrats into a revolutionary and an opportunist wing, into a Mountain and a Gironde, which did not appear only yesterday, nor in the Russian workers’ party alone, and which no doubt will not disappear tomorrow.”

This blunt assessment provoked further outrage from the Minority when the pamphlet was published in May 1904, but the stormy years ahead, and the eventual split between the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, would prove the truth of Lenin’s prognosis.

While the 1903 Congress produced sharp divisions between the revolutionary and opportunist wings of the party, these primarily revolved around the attitude towards organisational principles. It took the test of events – above all of the mighty revolutionary events of 1905 – to bring out clear differences over the political perspectives and tasks for revolutionaries in Russia. The differences which emerged in that pivotal year were brought out and sharply analysed by Lenin in another key work, Two Tactics of Social-Democracy, which we will delve into next week.