The announcement at the recent BRICS summit that this bloc of countries would be expanded to include six new countries generated a wave of optimistic, almost pious statements from prominent leaders of the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP), extolling the virtues of this enlarged group of countries from the so-called ‘Global South’.

[Originally published in Portuguese at colectivomarxista.org]

António Filipe, a former MP and member of the Central Committee of the PCP, wrote in Expresso that the “growing multipolarity of the BRICS represents a possibility for each country to obtain support for development without being subject to imperial tutelage […] This is good news for the world and will not fail to have a significant impact on the development of social struggles.”

In the pages of Avante!, the official newspaper of the PCP, we also find public praise for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from PCP Central Committee member Luís Carapinha. He celebrates the CCP as the “driving force behind major international cooperation and investment projects […] Initiatives that, together, lay the foundations for the transition to a new era of more equitable global development, the embryo of a new international economic order.”

His panegyric to the CCP ends, however, with an important warning: “There are struggles to come in order to transform the converging economic interests of the Global South – and its peoples – into effective methods of cooperation. This must be done, without ever losing sight of the main enemy at any given moment.” We communists, in fact, never lose sight of the main enemy: the bourgeoisie, in each and every “given moment”.

BRICS

It cannot be denied that in recent decades there has been a significant development of the productive forces in the countries known as the BRICS. From a Marxist point of view, this is no bad thing – quite the opposite! By developing industry, the capitalist class strengthens the working class and ultimately creates the conditions for its own overthrow. Economic development and the expansion of industry help to advance the tasks of socialist revolution in these countries.

It should be made clear that the BRICS is not a charitable organisation, but a group of countries – so-called “emerging economies” – that have come together in order to flex their growing economic muscle to influence world politics. The ruling classes of the BRICS member states have no interest in “more equitable development”. Rather, like the ruling classes of all capitalist nations, they want a bigger share of this “development”, i.e. world trade, for themselves.

Membership of the BRICS does not erase the class differences within a country, nor does it dispel the contradictions of capitalism or provide any solution whatsoever to the current crisis. So… what kind of “significant impact” can the BRICS have on social struggles or the living conditions of the working class?

For communists, “more equitable global development” can be achieved by the class struggle and the seizure of power by the proletariat alone. It cannot be achieved by a club consisting of Iranian imams, Egyptian generals, Brazilian capitalists, Saudi princes, Russian oligarchs and Chinese bureaucrats.

Imperialism(s)

It is precisely the development of capitalism that of necessity leads to imperialism, capitalism’s highest stage / Image: Presidential Press and Information Office, Wikimedia Commons

It is precisely the development of capitalism that of necessity leads to imperialism, capitalism’s highest stage / Image: Presidential Press and Information Office, Wikimedia Commons

It would be a mistake to present the world as if it were made up of only two types of nations: on the one hand, a group of imperialist powers (the USA, Europe and Japan) and, on the other hand, all the poor, underdeveloped countries, which are totally dependent on the so-called ‘West’.

According to this point of view, the latter countries cannot play an independent role in world politics or the world economy; their actions are entirely subordinate and dependent on the major imperialist powers (mainly the US), and as such, they can never be considered imperialists.

This way of looking at things ignores reality. Can we, for example, place Ethiopia, Bolivia or Bangladesh on the same level as Russia and China? It is clear that these countries are at very different levels of economic development. And with varying economic development comes varying capacity to assert their other interests: their desire to gain a greater share of world markets, greater access to oil and other raw materials, prestige, military power, and so on.

It is precisely the development of capitalism that of necessity leads to imperialism, capitalism’s highest stage. More than one hundred years ago, Lenin explained that the balance of forces between the imperialist powers was not immutable:

“Half a century ago Germany was a miserable, insignificant country, if her capitalist strength is compared with that of the Britain of that time; Japan compared with Russia in the same way. Is it “conceivable” that in ten or twenty years’ time the relative strength of the imperialist powers will have remained unchanged? It is out of the question.”

In Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, Lenin defined the five fundamental features of imperialism:

- The monopolisation of the economy.

- The fusion of banking and industrial capital to create “finance capital”.

- The export of capital.

- The international association of capitalist nations.

- The dividing up of the world – at the time through direct colonisation and today through neocolonialism – into “spheres of influence”.

Can anyone deny that the growth of monopolies, the domination of finance capital, the export of capital, involvement in international associations, and hunger for new markets are applicable to Russian or Chinese capitalism today?

Let us compare with the historic example of Portugal. During the dictatorship of the Estado Novo, the PCP said (correctly) that Portugal was both a colonising and a colonised country. If it was possible at that time to characterise the poorest and most backward country in Western Europe as both a dependent nation and at the same time imperialist, why can we not characterise Russia or China today as countries with imperialist ambitions and policies, despite the fact that the United States remains the world’s most important imperialist power?

And here we have to be crystal clear: acknowledging the imperialist character of Russia and China does not diminish the fact that the US government is the most reactionary force on the planet. For this reason, we are irreconcilably opposed to US imperialism. In the last 30 years alone, it has bombed or invaded Somalia, Sudan, Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria. We can add the countless instances of interference, blackmail, sanctions, coups d'état and ‘colour revolutions’ sponsored by the US government in the same period.

But US capitalism is not uniquely evil. It has taken on its role as the foremost imperialist power, due to its position as the largest capitalist power in the world. Today, the United States – itself a former British colony – is playing the role that Britain played in the 19th century. This role could be played by another country tomorrow, if the United States were supplanted as the most advanced and powerful capitalist country. This is because, at the end of the day, what counts are not the declared interests of the capitalists, but the historical laws of the development of capitalism.

The question is therefore posed: has the character of imperialism changed since Lenin’s time, since the days when Portugal was both a colonising and a colonised country? Or is it the PCP’s position on imperialism that has changed?

The role of China

The fact that China is governed by a party that formally calls itself ‘communist’ doesn't therefore make its economy socialist. On the contrary, the bureaucratic clique that dominates China has led the restoration of capitalism over the last few decades. This has happened through a policy of widespread privatisation, the liberalisation of the internal market and foreign trade, and an opening up to foreign investment on an unprecedented scale – it is now the country in the world that attracts the most foreign investment.

China’s economic development was based upon decades of economic planning under a nationalised economy. But that time has now passed. Today, the private sector contributes 60 percent of China’s GDP, accounts for around 60 percent of investment, generates more than 80 percent of jobs in the cities, and makes up around 80 percent of the country’s total businesses. Are these the characteristics of a socialist economy?

In Portugal, after the Carnation Revolution, the entire banking and financial sector, as well as the main industries, had already been nationalised. However, despite the size of the public sector (and even elements of self-management in some areas), Portugal never ceased to be a capitalist country. The nationalised companies operated according to the standards and norms of the market economy, as opposed to those of an economic plan decided upon and implemented democratically by the workers.

A country’s foreign policy is the external manifestation of the interests of its ruling class / Image: Press Information Bureau, Wikimedia Commons

A country’s foreign policy is the external manifestation of the interests of its ruling class / Image: Press Information Bureau, Wikimedia Commons

What we have in China today is a highly-centralised state, which maintains firm control over aspects of the capitalist economy, as well as the country’s important public sector. The character of the state’s role in the private economy is a hangover from the revolution of 1949. Who can forget Deng Xiao Ping’s famous slogan, “get rich!” – taken from Bukharin – which the Chinese bureaucrats chanted in the 1990s? Shortly afterwards, in 2001, it was Jiang Zemin’s turn to openly call on capitalists to join the Communist Party, at a time when more than 100,000 entrepreneurs were already members.

Those that argue that Lenin too, after the Russian Civil War, advocated the application of the New Economic Policy, which allowed a certain liberalisation of the Soviet economy, must not lose sight of the fact that the NEP continued to leave the main economic levers in the hands of the state. The NEP was also applied in very special circumstances: the country had been devastated by war, was completely surrounded by imperialist powers, and the NEP was seen as a temporary policy to buy some time until the triumph of the communist revolution in western Europe.

China’s pro-capitalist policies are anything but temporary. They have lasted for decades. Key sectors of the economy have been privatised and the leaders of the CCP are not calling for world revolution, but for Chinese capitalists to join their Party. Can anyone imagine Lenin advocating that the Russian bourgeoisie join the Bolshevik Party? And in the question of the regime we find another major difference: despite the threat of bureaucratisation that hung over the Soviet state in the 1920s, the system of workers’ democracy and freedom of discussion that existed in Russia at the beginning at that time cannot be compared with the monolithic Chinese regime.

Finally, a country’s foreign policy is the external manifestation of the interests of its ruling class. The so-called Belt and Road Initiative is often presented as an example of the different relationship that China wishes to establish with other countries, compared with the United States.

That China wants to build ports, roads, railways, airports and infrastructure and other ‘productive’ investments in other countries is nothing ‘innovative’ – it is the export of capital! China provides loans that will supposedly be used for projects and investments by Chinese companies, just as the British built railways in India at the expense of the Indians. In neither case is the intention to unite the peoples and regions of the country, but to plunder their resources and sell them products manufactured back home.

The fact that China can now offer more favourable conditions for lending is not due to the imagined beneficence of the Chinese state, but due to the need to remain competitive and conquer new markets from the United States and its allies.

A fairer world order?

Leaving aside, for a moment, the true nature of the BRICS countries, their defenders often focus on the “fairer development” that this association could bring about.

To put it simply, however, capitalism is in crisis. This crisis is the result of the contradictions and limits of the system. In recent decades, economic growth has been the result of cheap credit and the development of world trade.

But what accelerated growth in the past has today become an enormous brake. The world economy is increasingly polarising into two competing blocs as a result of the economic rivalry developing between the US and China. This is already rapidly evolving into an open trade war, with the introduction of measures such as tariffs, sanctions and restrictions on access to cutting-edge technologies. World trade is therefore threatened by a growing wave of protectionism, in which each country will attempt to export the crisis to its neighbours. And the bill for this protectionism, for the increasing costs of supply chains and of production, will ultimately be passed on to the consumers, in other words, the working class!

In this context, how can we talk about a “fairer world order”? And for whom would such a world order be “fairer”? For the emirs of Dubai? Or for the immigrant workers from South-East Asia who are exploited by Emirati capitalists to a degree bordering on slavery?

Between 2009 and 2022, the GDP of the United States rose from $14.47 trillion to $25.46 trillion. Yet the minimum wage remained at $7.25 an hour. What benefits have the American working class reaped from all the wealth produced in their country, from all the resources that ‘their’ capitalists have plundered all over the world?

Even if the BRICS countries managed to conquer a greater share of world trade, or benefited from so-called de-dollarisation and disentangle themselves from western-dominated financial institutions, within class society, the creation of more wealth does not automatically mean a fairer redistribution of income. And in the middle of a capitalist crisis, such an expectation is nothing more than a pipe dream!

The theory of ‘Permanent Revolution’

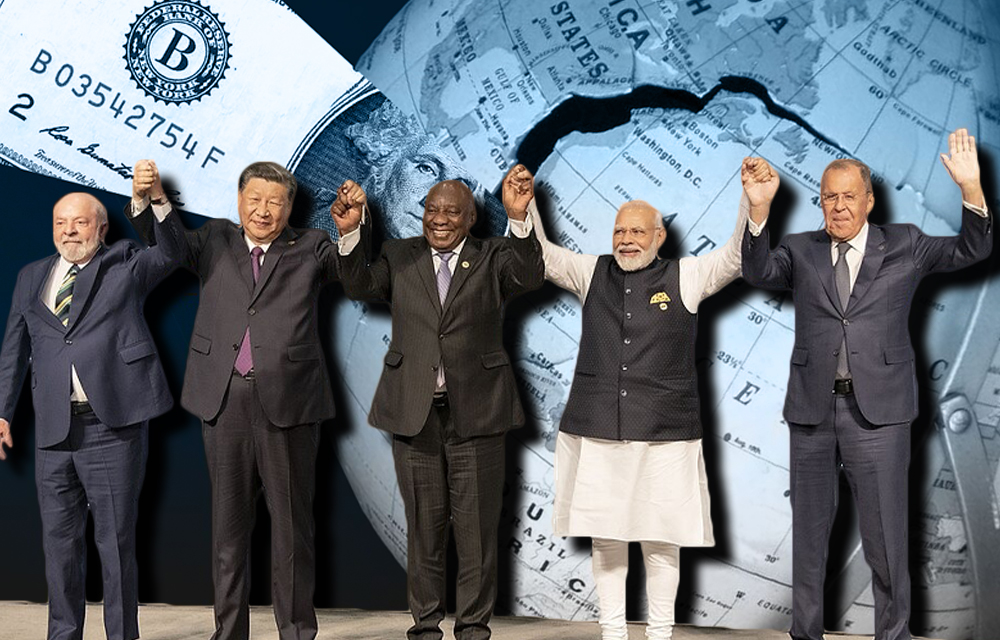

The creation of more wealth does not automatically mean a fairer redistribution of income / Image: 15th BRICS SUMMIT, Flickr

The creation of more wealth does not automatically mean a fairer redistribution of income / Image: 15th BRICS SUMMIT, Flickr

Following the Menshevik-Stalinist ‘Popular Front’ tactic, after the Second World War the communist parties advocated alliances with the so-called ‘progressive’ bourgeoisie of the colonised countries in the struggle against the colonising powers. Supposedly, in the colonised countries, there would be a layer of ‘anti-imperialist’ capitalists, with whom the peasant and proletarian masses could ally in order to win independence. But always and everywhere, the so-called ‘democratic’, ‘progressive’ or ‘anti-imperialist’ layer of the bourgeoisie never lost sight of the fact that the proletariat and the oppressed masses were its main enemy.

The utopian nature of this idea has been exposed repeatedly by the many successive defeats suffered by revolutionary movements, and the crushing of popular uprisings. The Popular Front was helpless to prevent the neocolonial domination of those countries which were freed from direct colonial rule. The belief that the capitalist class can play a supposedly ‘progressive’ role in the so-called Global South is not only misguided but reactionary.

Before 1917, although it was an imperialist power, Russia was also a relatively backward and dependent country. Despite the existence of pockets of highly-advanced, giant industry, most of the country had changed little since the days of serfdom, and the peasantry remained subjugated to the agrarian nobility. In developing the theory of the Permanent Revolution, Trostky explained that in a backward country in the epoch of imperialism, the ‘national bourgeoisie’ was inseparably linked to the remnants of feudalism and to imperialist capital. This makes them completely incapable of carrying out any of their historic tasks.

As Trotsky predicted, the corrupt Russian bourgeoisie was incapable of solving the most pressing tasks posed by history, particularly the agrarian question. It was for this reason that the Bolsheviks were able to seize power on the basis of slogans with an essentially bourgeois-democratic content, such as demands for “peace, land and bread”, for a Constituent Assembly, the right to oppressed nationalities to self-determination, and so on. But having taken power into their own hands, the Russian workers did not stop there. They proceeded to expropriate the capitalists and began the task of the socialist transformation of society.

Similarly, due to the endemic weakness of the national bourgeoisies of the so-called ‘Global South’, as well as their ties to imperialism, these capitalists will never be able to fulfil their historic tasks. They will always remain the servile agents of the great powers – whether they are based in Washington or Beijing.

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels wrote: “the emancipation of the workers must be the act of the working class itself”. It was from this perspective that, in 1917, the Bolsheviks organised the Russian working class and led it in the struggle against the reactionary Tsarist nobility, against the so-called ‘liberal’ Russian bourgeoisie, and against the imperialist powers of both the Entente and the Central Powers.

Yesterday as today, we communists hold the perspective that “the emancipation of the workers must be the act of the working class itself” – theirs and no one else’s!