Following the article on James Joyce’s Ulysses, published in issue 39 of In Defence of Marxism magazine, Hamid Alizadeh of the IDOM editorial board writes on Joyce’s Dubliners: a masterful critique of the paralysis, hypocrisy and alienation of Irish bourgeois society in the 20th century, which epitomised the ferment brewing in Ireland in the years prior to the Easter Rising of 1916.

Letter from an editor: James Joyce’s Dubliners

“When the soul of a man is born in this country there are nets flung at it to hold it back from flight. You talk to me of nationality, language, religion. I shall try to fly by those nets.”[1]

―James Joyce

As I was reading John McInally’s article on the centenary of James Joyce’s Ulysses in preparing issue 39 of the In Defence of Marxism magazine, I was drawn to read Joyce for myself. There could hardly be better proof that the article served its purpose to the fullest: to expand the horizons of our readers and assist them in delving into the great treasures of world literature.

So, after a bit of research, I decided to start with Joyce’s first major work, Dubliners, an unassuming book of fifteen short stories, which according to Joyce run in the order of “childhood, adolescence, maturity and public life”, each depicting everyday episodes in the lives of ordinary Dubliners, told in simple and plain language.

But looks can be deceiving. Behind the book’s innocent outward appearance, I discovered a deeply penetrating and razor-sharp critique; a damning indictment, not just of Irish society circa 1900, but of capitalist society itself. As Joyce himself put it:

“For myself, I always write about Dublin, because if I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world. In the particular is contained the universal.”[2]

Paralysis

“There was no hope for him this time: it was the third stroke.”[3] These are the opening shots of the first story, ‘The Sisters’, which depicts the legacy of Father Flynn, a Catholic priest who, towards the end of his life, appears to have lost his faith, along with his sanity. The story offers a fitting metaphor for the senility of the Catholic Church in Joyce’s Ireland and the weight that its veritable dictatorship imposed on its people.

Joyce’s narrator, a young boy who is under the influence of Father Flynn, continues in the same opening paragraph:

“...I said softly to myself the word paralysis. It had always sounded strangely in my ears, like the word gnomon in the Euclid and the word simony in the Catechism. But now it sounded to me like the name of some maleficent and sinful being. It filled me with fear, and yet I longed to be nearer to it and to look upon its deadly work.”[4]

In these heavily loaded lines, Joyce formulates his mission statement: to look into the “deadly work” of the “maleficent” and “sinful” paralysis covering the Irish nation, which he proceeds, calmly and methodically, to dissect and examine over the course of the following fifteen stories. His critique is made all the more powerful by his spiteless and undramatic style, which leaves no excuses to reject him out of hand.

Childhood

Leon Trotsky once noted that the idealisation of childhood as a time of peace, happiness and freedom belongs to the realm of privileged and aristocratic literature. “Life strikes the weak,” he wrote, “and who is weaker than a child?”[5] In Dubliners, childhood is presented as it is for most people: a time of fear, uncertainty and oppression.

In the chilling story of ‘An Encounter,’ we are introduced to a group of adventurous school boys, full of vitality, joy, and playful curiosity. They like playing cowboys and Indians, and reading American magazines and detective stories. We learn, however, that their naturally childish behaviour is not condoned. The narrator recounts an episode where Father Butler, their teacher, shames and scolds one of the boys for reading American comic books rather than studying the Roman Empire.

One day, in an attempt to escape the heavy atmosphere of their familiar surroundings, some of the boys decide to skip school and go on an adventure through Dublin. But the world outside offers little respite. At first, our adventurers are verbally attacked by two other little boys from poor backgrounds, who mistake them for Protestants – a harsh reminder of the class divisions in society and the reactionary role of religious sectarianism.

Passing the first danger, the main characters eventually run into a greater one. An older man approaches. He appears to be warm and friendly. But gradually we begin to discern that he is in fact seriously disturbed, and has sadistic and perverse tendencies. Joyce brilliantly conveys the nervous tension and anxiety that creeps over the narrating little boy, before he manages to break away from the old man.

A close call, perhaps. No crime has taken place. And yet, unspeakable damage has been done. The day started as an adventure, an attempt at liberation, but ends with the boys feeling more entrapped and isolated than before. There is no escape.

The casual way the story is told merely tells us that such episodes happen all the time, and over time, the fire of life and adventure that every child is born with, is gradually extinguished. Its place is taken instead by shame, fear and… paralysis.

The simple premise posed in the beginning of the book, is allowed to develop into its full stature as the book moves from childhood to adolescence, and then adulthood. The stories are not carried by bombastic drama, but by the subtle, yet violent struggle between the inner life force of Joyce’s characters and the morality of the existing order.

Like the lotus feet of the decrepit Chinese aristocracy, his Dubliners are gradually broken, bound and squeezed into stiff and narrow moulds that are far too small for their souls. They grow to be deformed creatures, who find themselves alienated from society, from one another, and even from themselves. Nevertheless, Joyce always shows us the embers of humanity still alive underneath it all and ceaselessly trying to find a way to the surface. It is precisely that human spirit that Joyce wishes to awaken with his work.

The Church

“...the plague of Catholic[ism]… the vermin begotten in the catacombs issuing forth upon the plains and mountains of Europe. Like the plague of locusts described in Callista they seemed to choke the rivers and fill the valleys up. They obscured the sun. Contempt of [the body] human nature, weakness, nervous tremblings, fear of day and joy, distrust of man and life, hemiplegia of the will, beset the body burdened and disaffected in its members by its black tyrannous lice.”[6]

The Catholic Church receives a particularly thorough undressing throughout Dubliners. At the end of ‘Counterparts’, for instance, the main character, Farrington, a failure and a drunk, comes home one evening to find that only his small children are there, one of whom tells him that their mother is at the chapel. Finding no food, and with the fire having gone out, Farrington unleashes his pent up frustrations on his little boy, whom he vigorously strikes with a stick. The terrified little boy gets on his knees begging, “O, pa!… Don't beat me, pa! And I’ll… I’ll say a Hail Mary for you… I’ll say a Hail Mary for you, pa, if you don't beat me… I’ll say a Hail Mary…”[7]

The heartbreaking, fruitless and humiliating attempt at appeasing his monstrous assailant is clearly a metaphor for the relationship that Joyce sees between the Irish people and the Catholic Church.

Against the stream

Joyce puts Irish bourgeois society to the test, and finds it lacking: the church, hypocritical and oppressive; bourgeois nationalism, impotent and cowardly; the petty bourgeoisie, ignorant and narrow-minded.

Page up and page down, he meticulously demystifies all the moral pillars of Irish society: religion, tradition, nation and class – nothing escapes scrutiny. And gradually, the book proves that what appear to mankind as independent, mythical and timeless entities, are nothing but the products of human relations themselves.

The moral decay portrayed in Dubliners merely reflects the degenerate and conservative nature of the upper echelons of society, which stood in direct opposition to the needs and aspirations of the masses. This was fully revealed in the revolutionary events of the Easter Rising in 1916, which was thoroughly betrayed by these same upper layers. Incidentally, while not dismissive of it, Joyce did not outright support the rising. His work, however, can be seen as a part of the general ferment anticipating these events, with a crisis of the old ideas and the rise of new revolutionary ones.

Indeed, although he did not explicitly state this, Joyce’s ideas were nothing but revolutionary. Like the little boy in the fairy tale who proclaims that the emperor is naked, he exposed the true, monstrously reactionary nature of the status quo, under the weight of which the souls of the Irish people were being crushed. For that, the establishment never forgave him. He spent the bulk of his life in self-imposed exile, which he saw as the only manner in which he could practise his art. Throughout his life he was harassed by the church and other authorities, both in Ireland and elsewhere too. In fact, it took him nine years to get Dubliners published, after unsuccessfully approaching countless publishers.

The correspondence with Joyce’s main publisher reads like an additional chapter of the book, revealing the suffocating influence that the establishment exerted over culture and the cowardice of the petty bourgeoisie. In letter after letter, the publisher attempts to censor different aspects of the book to avoid offending bourgeois public opinion. Joyce stands his ground and insists that what he has written is nothing spectacular, but merely what is.

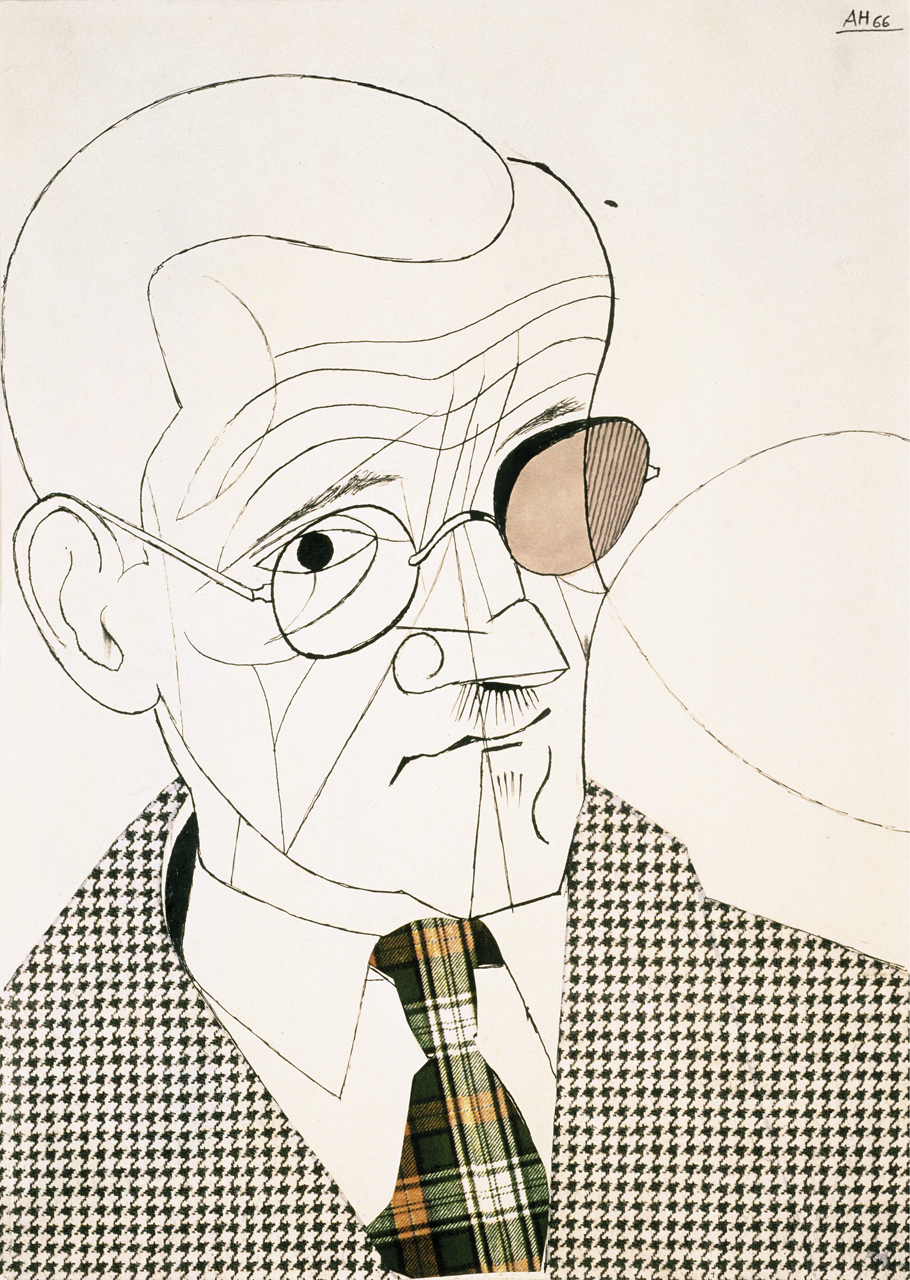

Although not explicitly stated in his art, Joyce's ideas were revolutionary: he sought to plainly state what was in rebellion against the status quo / Image: Adolf Hoffmeister

Although not explicitly stated in his art, Joyce's ideas were revolutionary: he sought to plainly state what was in rebellion against the status quo / Image: Adolf Hoffmeister

In a letter from June 1906 he wrote: “I seriously believe that you will retard the course of civilisation in Ireland by preventing the Irish people from having one good look at themselves in my nicely polished looking-glass.”[8]

What makes this work stand out is precisely the blunt manner in which Joyce’s Dubliners are portrayed as what they are, what they are made to be. The image is not very flattering. The characters often appear pathetic, weak, at times even sick and disturbed. But there is no malice on Joyce’s part. In fact, one senses a deep respect and compassion for the damaged people of his country.

What we have is not the aimless, nihilistic ‘critique’ of a postmodern writer, but the exact opposite. It is a revolutionary act, a rebellion of enlightenment, a lifting of the veil of hypocrisy and deception and looking reality straight in its face.

“I fight to retain [the original text]” he wrote to his publisher, “because I believe that in composing my chapter of moral history in exactly the way I have composed it I have taken the first step towards the spiritual liberation of my country.”[9]

‘The Dead’

In his unfinished autobiographical novel, Stephen Hero, which was written around the same time as Dubliners, Joyce describes his own ambition to be “the voice of a new humanity, active, unafraid and unashamed.”

We come closer to this voice in Dubliners’ final and longest story, ‘The Dead’. This brilliant work has been dubbed by many as the greatest short story ever written. I would agree. ‘The Dead’ is an endlessly thought-provoking treasure that can be read again and again. Here, Joyce takes a different tone to the rest of the book, focussing instead on the beautiful sides of Irish culture: the familiarity, the joyfulness and the hospitality which finds room in its heart for everyone.

The story also gathers the threads that have previously been laid out for us, when at the end, the main character, Gabriel, experiences an epiphany after having been through an evening of disappointments and personal defeats. As a result, he sees all that he took for granted in life, all that he based himself on, whether it be his political views regarding Ireland, his moral principles or his relationship with his wife, fall apart. His old ideals and illusions about life and about society lie in ruins and consequently so does his self-image.

Joyce takes us through the emotional pain that such an all-encompassing blow inflicts on a person; the heavy heart that such a stark realisation conjures. And there is no turning back. Life will never be the same again. Indeed, because in reality, Gabriel’s life is only just beginning. Finally he is facing the world and seeing it all, with open, unclouded eyes. He is painfully aware of the deep wounds within himself and his society. But the demise of his illusory freedom, the understanding of his conditions, is also the beginning of his real freedom. He will go into tomorrow as a new man; the paralysis is broken. The story ends with these beautiful words:

“It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.”[10]

Truth

Joyce is a master. His work is brimful of meaning and life lessons. But at no point do you feel that he is lecturing or pushing towards a certain conclusion. Not once does he bend the storylines for the sake of moralising or in order to squeeze in a political or philosophical point. Such ‘political’ art is tiresome at best, but cringeworthy for the most part. Joyce rejects idealising art. He follows his art where it takes him. But this is not an abstract, untethered “art for art’s sake”.

“(...) I have written it for the most part in a style of scrupulous meanness” he retorted to his publisher who wanted him to censor parts of the book, “and with the conviction that he is a very bold man who dares to alter in the presentment, still more to deform, whatever he has seen and heard. I cannot do any more than this. I cannot alter what I have written.”[11]

Joyce presents us with what he sees, and we are left to draw our own conclusions. The point, however, is that he has a supremely clear vision, an encyclopaedic knowledge of culture and a sublime control over the English language. Yet his work oozes politics, philosophy and moral lessons because he manages to capture the living essence of humanity itself; the inner principle that drives us on a day to day basis, our desires and aspirations, and our relationship to wider society. “Art is true to itself when it deals with truth,”[12] he once said – and Joyce does indeed show a glimpse of the real, living, struggling truth of humanity in the present epoch of capitalist decline. In this he has done an inestimable service for those who struggle for a better world today.

Notes:

[1] J Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Wordsworth, 1992, pg 203

[2] A Power, “James Joyce - The Irishman”, The Irish Times, 30 December 1944

[3] J Joyce, Dubliners, Penguin Books, 1996, pg 9

[4] ibid.

[5] L Trotsky, My Life, Wellred Books, 2018, pg 1

[6] J Joyce, Stephen Hero, New Directions, 1963, pg 194

[7] J Joyce, Dubliners, Penguin Books, 1996, pg 98

[8] R Ellman (ed.), Selected Letters of James Joyce, Viking Press, 1975, pg 90

[9] ibid., pg 88

[10] J Joyce, Dubliners, Penguin Books, 1996, pg 223

[11] R Ellman (ed.), Selected Letters of James Joyce, Viking Press, 1975, pg 83

[12] R Ellman (ed.), Selected Letters of James Joyce, Viking Press, 1975, pg 83